The Borans and the Honeyguide Bird

Nature has a plethora of examples of mutualistic relationships that create win-win scenarios. One that I am particularly fond of involves the Boran people of Africa, and a bird known as the Honeyguide.

Human hunting parties are often joined by the Honeyguide which leads them to bee colonies. In unfamiliar areas, the average search time was 8.9 hours without the Honeyguide and only 3.2 hours when guided by the bird. Borans use fire and smoke to drive off the bees, break open the nest and remove the honey, but leave larvae and wax behind. The bird gains access to larvae and wax. The use of fire and smoke reduces the bird’s risk of being stung, and the nests are more accessible to humans. According to the Borans, the Honeyguide informs them of direction, from the compass bearing of bird flight; distance, from the duration of the bird’s disappearance and height of perch; and arrival, by the “indicator call”. Birds and Borans can survive without the other, but they are much more efficient with each other, resulting in a win-win.

This example of mutualism in nature is instructive for our understanding of interdependence in our diversity and inclusion work.

As I continue to promote the “business case” for diversity and inclusion, the reality of our interdependence is the most compelling argument that we will need to make in the future. In order for the planet to survive, we have to come to leverage our connections for the greater good of all.

Inclusion is not just good for business, it is necessary for the survival of business. Relationships in the future will have to be built much more on our need for each other than just an altruistic mission.

There are numerous studies that conclude that cooperation promotes higher individual achievement and greater group productivity than do individualistic or competitive solutions.

One of the most illuminating examples of interdependence is the global plight of women. Economists agree that the world economy will continue to be stymied if women do not make economic gains. In the Global D&I Tipping Point we reference a 2012 Booz and Company study that asserts if overall employment rates for men and women were equal the GDP in the United States would increase by 5 percent. In Japan, the increase would be 9 percent, and in developing countries like Egypt, GDP would increase as much as 34 percent. The findings indicate “that the economic advancement of women doesn’t just empower women but also leads to greater overall prosperity”.

Another example is the education pipeline which we wrote about two weeks ago. If students don’t achieve, there will not be enough skilled workers. If there are not enough skilled workers, the economy will surely suffer. The interconnections are clear.

From an organizational perspective, operating interdependently would lead to greater performance. Strategy Guru C. K. Prahalad, who until his death in 2010 was the distinguished University Professor of Corporate Strategy at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business in the University of Michigan, offered that successful organizations of the future would not envision themselves in a fixed linear hierarchy but rather as networked and interconnected.

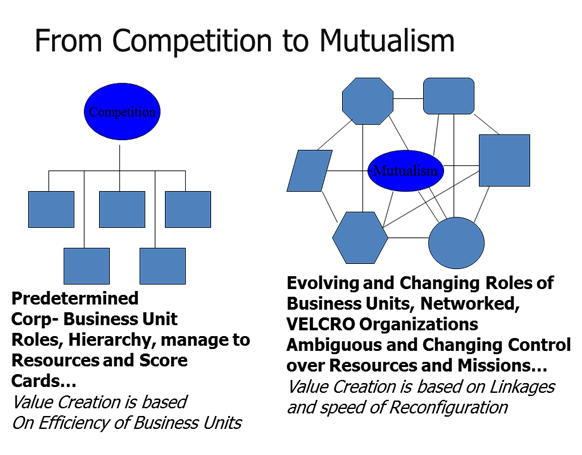

The diagram below shows on the left, the more common, current competitive organizational culture based on independent thinking, and on the right, a mutualistic structure based on multi-dimensional thinking. In the competitive model, there are pre-determined, fixed business units, hierarchies, and roles. The structure is linear, manages to the resources within the silo, and the measures of success are narrow and often disconnected from whether they truly contribute to the overall enterprise’s success.

In contrast, if an organization recognizes its interdependence, it would form more like the second diagram as a network . . . with flexible roles, situational control, and an organizational structure like velcro, able to be reassembled quickly to meet ever-changing circumstances and marketplace opportunities. Value is measured based on the synergistic impact of the multiple linkages and how quickly the mutually dependent structure can be reconfigured to generate value for all interrelated parties – customers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, the environment – rather than just a limited set.

If we really understood the “interrelated structure of reality”, there would be no organizational silos, no “us and them” mentality, less disparities among the have and the have nots and no dominant/non-dominant group power inequalities.

Implications and Recommendations for Diversity and Inclusion Practitioners:

As the world becomes flatter and more intimately linked globally, interdependence becomes a more critical concept for diversity and inclusion practitioners to understand and advocate for. We come from a strong competitive way of being in all aspects of society from politics to sports, which perpetuates “us and them” thinking. Therefore this shift to a more interdependent way of thinking, being and doing will not be easy.

D&I practitioners will need to become savvy systems thinkers. Systems thinking is the process of understanding how things, regarded as systems, influence one another within a whole. In organizations, systems consist of people, structures, and processes that work together to make an organization “healthy” or “unhealthy”. For example, understanding how the current pieces of the HR system work to support or not support D&I goals is a critical first step. How does talent acquisition work with talent development? What role is employee relations playing in the bigger picture?

Often when you take the pieces apart to understand them independently you get an interesting picture of how they might not be working synergistically to achieve the overall goals for D&I. Systems thinking helps us understand how seemingly unrelated events or activities, that may be separated by time and distance, actually impact the functioning of the entire system. Systems thinking problem solving processes allow you to understand and examine patterns that influence outcomes.

The role of the D&I practitioner is becoming more complex and we need additional tools, such as systems theory, to more effectively perform our roles. Seeking to understand interdependencies from a global and big picture perspective will help us better see where the “breakdowns” in the system are occurring. It is a disciplined process of analysis that we should add to our tool kits.