I want to use this post to briefly (re)introduce two very familiar concepts to you—race and ethnicity. My hunch is that the reader already has in her mind some idea of the definition of, and difference between, both concepts but in light of several recent headlines I think it’s useful to clarify a few things. Discussion around these two terms is common fodder for most college level sociology classrooms and it was no different for the ones I taught for several years. And I can distinctly remember telling my students something like, “I know the difference between race and ethnicity seems clear, but you’re going to encounter very smart people confusing them often in your lives.” I want to write about why that is.

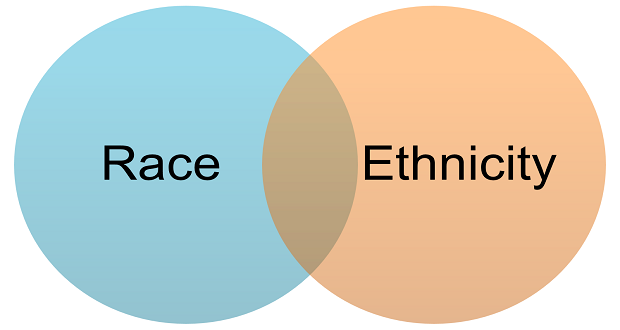

Part of the reason many people—myself included from time to time—consistently confuse race and ethnicity is because at their core, they are very similar. But the differences between them are also very important and worth continued efforts to distinguish them. The most commonly accepted definitions are that race is biological and ethnicity is cultural. Race is the term that simply describes physical differences (skin, hair, eye, ear, and nose shape etc.) And ethnicity describes a cultural identity that is tied to ones geographical region, language, food, heritage, values, beliefs, etc.—one’s culture. At this point in my life I best understand the similarities and differences with a Venn diagram (pictured above). I like this because the diagram allows for a much smaller space of shared similarities and larger spaces to represent the differences.

So first the similarities. Race and ethnicity are both socially constructed—which means that they don’t actually exist in the world as tangible realities. This is a little more complicated for race because we can obviously point to physical differences between people—skin, hair texture, height, eye, ear, and nose shape. But modern science has proven again and again that on the molecular level, it doesn’t make much sense to talk about distinct racial groups—human DNA shares many more similarities than differences. And the differences in our DNA that account for something like skin color are so insignificant, and widely diverse, that it’s practically impossible to pinpoint a “white” or “black” race in the gene pool—its endlessly complex. If you take any 10 people in a room and line up their forearms, you will have 10 different shades of color—from the myriad combinations of race genes that make us all unique. So when we say someone is black or white or brown this is a social convention we use to group people—but our actual skin tones are much more colorful and complex for such simple boxes. Ethnicity is also socially constructed. The boundaries around what makes someone Latino for example are more fluid than the rigid box on the census would have us believe. I have a friend who is Mexican American born in California who identifies strongly as Latino. She doesn’t happen to speak much Spanish, but her parents are Latino, she eats Mexican food, participates in Mexican traditions and values Mexican cultural norms—but where her Latino-ness and American-ness start and stop is not clearly defined—culture and ethnicity run deep and are complex.

This is where the important differences between race and ethnicity becomes important—at least how I currently understand them. In the Venn diagram above, I would put “socially constructed” in the area of commonality; but in the larger regions of difference I would say that race is institutionalized and outside of our control while ethnicity is much more open to our choice of cultural adoption. Race, especially in the US has been institutionalized throughout history so that certain races are seen and operate as more valuable and powerful while others are not. As I wrote about several weeks ago, there were historical groups of immigrants that are now considered racially white who were once discriminated against for being non-white—or not white enough. The arguments against including Germans, Jews, and Irish into official Whiteness had less to do with their ethnicity—their cultures—than it did with their race. The white supremacists of the day talked about their “dirty” white skin that was not as pure as their more Anglo neighbors and the size of their noses and heads were racial characteristics that pointed to their supposed inferiority. In short, they had no choice about the whiteness of their skin—which for many of them was darker, more pink, or more freckled than other whites with more power. Since they could not change their skin—their race—they did have a choice on how they culturally identified—their ethnicity. And many of them decided to “give up” their ethnic heritage in place of a new cultural identity, “American.”

I share all of this to say that I think the differences between race and ethnicity still matter—especially since many folks continue to confuse them. The recent headlines around Rachel Dolezal’s so-called “transracial” identity and the Dominican Republic’s (a largely black/brown island) threat to deport other Dominican Haitians (black/brown people) bring to light the importance of making these distinctions. Although race and ethnicity are both social constructions, those social constructions matter for different reasons and to different degrees.