Last week’s feature asserted the importance of decentering the normative narrative, but doing so is just part of the ongoing process and work of equity. This week’s feature will focus on understanding the distinction between equity and equality.

First, consider this scenario:

[dropshadowbox align=”none” effect=”lifted-both” width=”auto” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]A house is on fire in your neighborhood. You call the fire department. The firefighters pull up and start spraying all the houses on the street at the same time instead of focusing on the one that’s actually on fire. The house burns down because there’s not enough concentrated efforts directed towards putting the fire out.[/dropshadowbox]

What just happened?

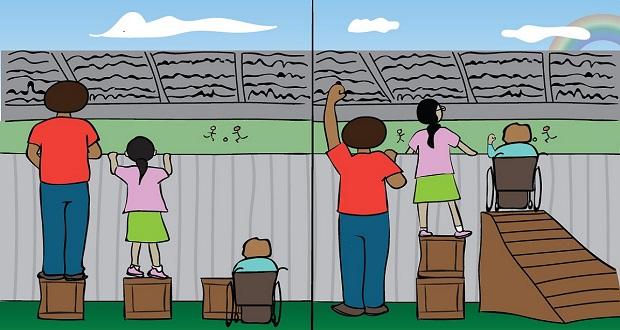

This scenario is often used to describe the difference between equality, which means that everyone gets the same thing, and equity, which requires that everyone get what they need according to their circumstances.

However, I prefer real life examples:

All lives matter versus black lives matter.

Colorblindness versus embracing and celebrating diversity.

Equal “access” to an exclusive and punitive healthcare system versus tangible and affordable healthcare options, regardless of your background or medical history.

As Black Lives Matter activist and educator Deray McKesson says, “The difference between equity and equality is that equality is everyone get the same thing and equity is everyone get the things they deserve.”

But for some people who are part of historically marginalized groups, getting the things they deserve takes more work. It takes more voices demanding from those in power to be noticed and heard.

During an AmeriCorps post-grad year of service, I worked at a social and racial justice organization in Ferguson, Missouri. We hosted various church and non-profit groups who wanted to understand what happened in our city in the fall of 2014 after Michael Brown was killed. They would arrive, take a look around, and say, “It just looks like a normal, quiet suburb here. How did it get to the point that we saw on the news – with all the tanks and screaming and burning?”

I would always respond that Ferguson is a place, like many other suburbs and cities throughout our country, where a portion of the residents, namely the black residents, were not getting everything they needed or deserved as citizens for a long time. Black residents who were struggling economically, socially and politically were not being heard by the rest of the normal – white, middle-class – Ferguson residents who just thought they lived in a nice, quiet suburb. So, when Michael Brown was killed by local policeman Darren Wilson and left in the streets for four hours, it was as if the city said to the black residents of Ferguson, “You have been right all along. We don’t care about you, and we don’t care about your children. We don’t care about protecting you, but we will protect the rest of the city, and its normalcy, from you.”

As anyone watching the news back in the fall of 2014 knows, many black residents of Ferguson, St. Louis, and around the country decided they would make it known that they were not getting what they deserved – that they were not being treated equitably.

As previous posts in this series have discussed, social justice work and staying woke involves correcting social and economic inequities. However, pushing for equity in a society that places a high value on meritocracy but a low value on people with marginalized identities is exhausting. It is also necessary.

Perhaps it is the precisely those with the most daunting pre-existing conditions who need the best healthcare options.

Perhaps it is precisely those who are running from violence and terror in their home countries who need the most protection in ours.

Perhaps it is precisely those whose love has been silenced or pushed to the side who need to celebrate their love the most.

Perhaps it is precisely those whose rights have historically been nonexistent who need the most protection of their rights.

Perhaps it is precisely those deemed the most academically or socially challenged who need the most attention and resources in the classroom.

Perhaps it is precisely those who do not see themselves at places of power in the workplace who need the most protection and encouragement to thrive.

None of this is to say that we all don’t deserve all the best healthcare options, protection, love, rights, education, and inclusion in the workplace. It is, rather, to say that some people already have what they deserve while some people still have to demand it.

Working towards equity and not just equality requires acknowledging this discrepancy and seeing another person and their situation clearly enough to understand that what works for one does not work for all. It begins with understanding that there are some in our society who have yet to be seen, and not for lack of trying nor for lack of worth.

As Mary Frances Winters says in We Can’t Talk About That At Work, we need to abide by the Platinum Rule rather than the Golden Rule: instead of treating others how you want to be treated, treat others how they want to be treated.

I am constantly challenged by this rule. It is a daily reminder that equitable systems are built by those who truly listen to one another well and act towards one another accordingly. How we listen to one another’s needs, hopes and fears affects if and how we demand that our institutions and organizations listen as well. It affects whether we notice those who aren’t getting what they deserve. It affects whether we are allies or simply bystanders.

Equity begins by asking yourself: Are you getting the things you deserve, and are you willing to stand with and elevate the voices of those who are not?