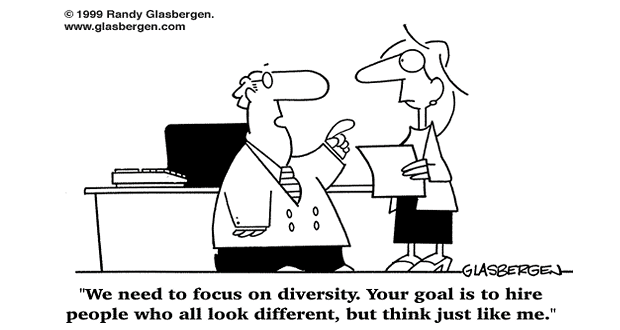

A number of years ago, I interviewed a CEO for a research project for a client. I asked him about what he looks for when he has an opening on his team. He told me that he always probed for how different the perspectives of the prospective candidates were from his own. “I want to hire people who have very different views from me. After all I understand my own worldviews. It does me no good to hire people who think just like me. I will not get to innovation with a team who all have similar world views.”

How many leaders actually intentionally hire people who they think are very different from themselves? We often hear the term “good fit” in the HR world. What does good fit usually mean? It generally means that I see a lot of commonalities in this person that would make it easy for them to “conform” to our culture. This leads to organizations hiring from specific universities (“we have had good luck with graduates from xxx”), or schools from a particular part of the world (e.g. Northeast United States, the UK).

[dropshadowbox align=”right” effect=”lifted-both” width=”250px” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]“In fact, more than half of the evaluators in the study ranked cultural fit—the perceived similarity to a firm’s existing employee base in leisure pursuits, background, and self-presentation—as the most important criterion at the job interview stage.” –American Sociological Review: Hiring as Cultural Matching: The Case of Elite Professional Service Firms, Lauren Rivera (2012)[/dropshadowbox]Research also shows that companies hire people who are more like them and who they would like to be friends with. Lauren Rivera, an assistant professor of management and organizations at Northwestern University, spent two years interviewing 120 people who were hiring entry-level candidates for several top law, investment and consulting firms.

She found that while the companies gave considerable weight to basic qualifications they also considered which university the candidate graduated from. In addition, a great deal of importance was placed on finding candidates who were a good “cultural fit” for the company. That often meant things like sharing a common interest in certain sports or extracurricular activities, or just being the type of person you’d be content to go on a business trip with.

The employment site Glassdoor collected 285,000 questions asked by hiring managers, and the following four rank among the 50 most common.

- What’s your favorite movie?

- What’s your favorite website?

- What’s the last book you read for fun?

- What makes you uncomfortable?

Over the last couple of years the site has found a significant rise in questions asked about cultural fit. What is the probability that a candidate from Prague is likely to have much in common around movie choices with an interviewer from Peoria?

Why Do We Seek Sameness?

We are steeped in a value system that fosters “common ground” thinking. “Let’s first explore what we have in common.” Rigid organizational cultures that unconsciously or consciously require conformity to narrow behaviors and norms that work well for only the dominant group thwart creativity and innovation that might come from those who are in the minority in the organization. I recommend that we turn the commonality norm upside down and “first explore our differences.” Not that similarities are not important, they are the easy way out. Stopping at similarities can lead to mediocrity.

Focusing on differences rather than similarities is a tough switch for most of us. We have been hard wired to seek commonality (“birds of a feather flock together”). Most of us approach differences by minimizing them.

Do you intentionally seek out vastly different perspectives from your own or do you unconsciously or consciously gravitate to people who are more like you?