I want to recommend a fascinating book to you that I’m currently reading, “The History of White People” by Nell Irvin Painter. Dr. Painter tells an untold and much needed story about the complicated history of the race that is too often altogether ignored or uncritically examined. The 400 page book is much too rich to summarize in this post, but I do want to share one of my big takeaways with you that I think is relevant for today: the difference between whiteness and White Supremacy. These are two different ways of talking about whiteness that weave their way through the book. And I think there is confusion about them in contemporary talks about race.

As I understand it, White Supremacy is an ideology, philosophy, and system of power that represents the historical access to power that whites have had throughout history. This is different, but not separate, from ground-level hate groups that claim that white skin is superior. White Supremacy is about policies, structures, and ideologies that continually propagate white forms of power and access. So for example, a white supremacist (hate group member) may claim to hate another race, but may not have much real power themselves (i.e. a lower class neo-Nazi). But an entire nation, government or economic system that privileges whiteness and denies other races is much more powerful. The way White Supremacy shows up in the book is in the myriad historical examples of whiteness fighting to become the standard of power, beauty, and intelligence through science, film, history books, and public policy. Painter goes to great lengths to tell the complex story of how whiteness became a race, but whiteness’s claim to power is a constant staple through time.

The second and more explicit way that Painter describes white people is by illustrating the deeply complex and vast varieties of people that make up the many shades of whiteness. This may be the most unique contribution of her book. Painter does what has rarely been done before: she complicates the idea that whiteness is monolithic and universal. Again, the examples of the shades of whiteness are far too long to list here, but the various stories of early German, Italian, and Irish immigrants who were once outcast as people who were not truly white are fascinating. Painter goes to great lengths to detail how these various groups experienced their own racial exclusions to White Supremacy while sharing very similar skin to the people who were writing and directing history. These are untold stories in history books where mentions of race usually refer to black and brown peoples. They are also important and relevant stories for contemporary conversations about race. Many whites today still identify with their particular cultural group (Italians, Dutch, Irish, etc.), but many do not. For many people, their cultural and ethnic heritage has been lost in the long trend of unifying and whitewashing whiteness.

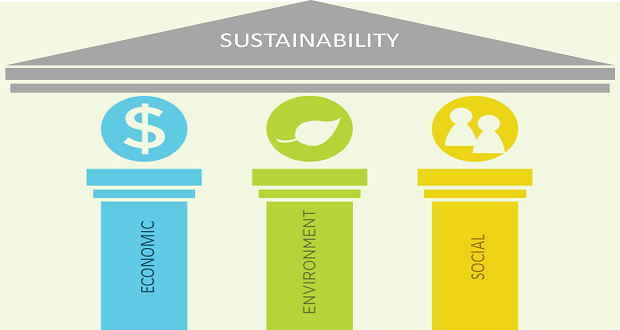

Although I do not think it’s necessary that all white people embark on a journey to recover their racial past, it is important to recognize that whiteness, like all races, was a product of a long, complicated history of solidifying into a race. It was socially constructed, with its own unique twists and turns—some more ugly than others. But what I think is most useful about recognizing the many shades of whiteness is the potential for challenging White Supremacy. When all the shades of white realize that many of their ancestors were once also once excluded from society as outcasts—and not white enough– then there can be greater solidarity for the social outcasts of all colors today.