This article was originally posted on Jamillah Karim’s blog, “Race + Gender + Faith” on April 6. It is reprinted with permission.

You would have thought I’d won some money if you had witnessed my excitement upon learning that I was selected to be featured in JET as a young faith leader in the Black community. That was in February.

It was perfect timing that the article came out in this week’s JET with Queen Latifah on the cover. Why? Because just Monday I received this tweet from Arabic Funk:

Where’s @IbtihajMuhammad@aminawadud Fatima Jackson@jamillahkarim Intisar Rabb?thrivalroom.com/32-photos-that…@SanaSaeed

The link in the tweet is Thrival Room’s (hadn’t heard of this site before) “32 Photos That Hope to Change the Way We Look at Muslim American Women.” The women profiled range from artists to educators to doctors.

BUT there was not one African American Muslim woman featured. The women appear to be of Arab and South Asian descent.

My first thought was that it demonstrated the continued relevance of my first book American Muslim Women, where I argue that African American and South Asian American Muslim women generally occupy separate ethnic spaces, though ummah ideals of unity and other social dynamics occasionally facilitate our crossing our race, class, and gender boundaries.

My children and the richness of life pulled me away from these thoughts until facebook returned them as African American Muslim women discussed what it meant to be left out again and as efforts were made to create alternative lists.

I want to say out loud that this glaring omission does matter in the sense that it unwittingly reinforces the narrow narrative of American Muslims as immigrant and proves the immense work we need to do to recognize one another across race and ethnic lines in the American ummah. But in another sense, it really doesn’t matter that we were left out because our community mothers and fathers, our leaders, our Ana Karims (you have to read my new book to learn about this amazing lady), our Tayyibah Taylors, our Ayesha K. Mustafaas, and our Qur’an Shakirs have been doing this work since we were babies.

Yes, images and books and lists are powerful and we need all of them to fight Islamophobia, but know that we’ve been in the trenches shattering the myth of the oppressed, deprived, foreign Muslim woman for some time now. And it’s paying off.

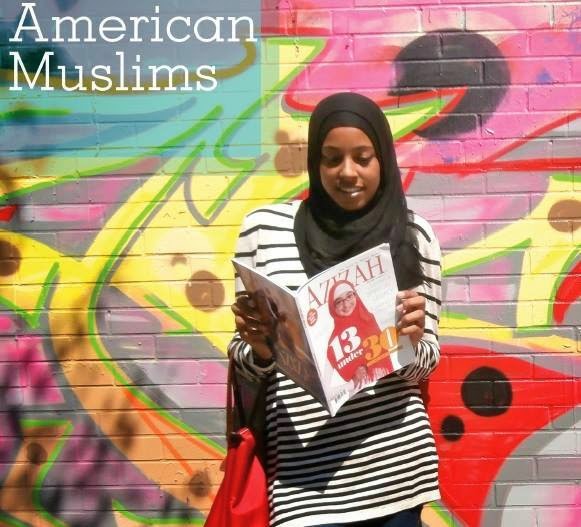

We have been featured in our own presses such as the Muslim Journal, but also in mainstream presses such as the New York Times. Just recently, the image of a Black woman first featured on a back cover of Azizah magazine was chosen by the U. S. Department of State for its 2014 publication on American Muslims.

For me, the greater achievement is when our media are recognized by the larger community, as in the case of Azizah Magazine, or when we are included in an important list by a publication that is not Muslim. And not because others are defining us, but because others find us valuable and relevant.

The JET article in which I am featured is titled “The Chosen Few”, and it reads, “With a passion for raising spirits, these new faith leaders inspire truth-seekers to listen for God in the still and the storm.” Each faith leader is introduced and quoted with words of wisdom on some aspect of human experience such as love or failure.

Alhamdulillah, I am the Muslim among the five faith leaders featured. Though the feature is small in print, the meaning of this is enormous because it demonstrates American Muslims’ ability to offer something beautiful and meaningful from our tradition to a larger human community beyond our faith. The great historian of Islam Marshall Hodgson notes that indeed this ability to offer something relevant to people is indication that a new religious tradition has succeeded in becoming an integral part of society.

Hodgson argues that the cultural traditions and dialogues within a place determine Islam’s cultural relevance: only as Islam engaged already existing cultural dialogues could it “become significant for cultural life at large.” To be included in JET‘s list and other mainstream media in positive, self-defined ways means that we have entered the dialogue and that we are valued.

But of course, our success started with creating our own value, our own images, but even as we created and promoted our own, we have been most effective when the mission is beyond establishing ourselves in this country, and showing compassion and concern for the people who were already here.

Two leaders, whom I highlight in my first book, come to mind most immediately in this light: Dr. Umar Abd-Allah who has encouraged Muslims to make the concerns of non-Muslim Americans their concerns and Imam W. D. Mohammed, whom Dr. Umar holds as a model of this principle.

Speaking to an audience largely second-generation South Asian and Arab Muslim, Dr. Umar stated, “You have to love your people. If you don’t love your people, how can you take Islam to your people? And how can you not love your people?”

Imam W. D. Mohammed loved his people.

The Nation of Islam created the Muhammad Speaks newspaper as a medium for Black Muslim expression and images. When Imam W. D. Mohammed became the leader of the Nation after his father’s death, he changed the name of the paper from Muhammad Speaks to Bilalian News. Imam Mohammed coined the term Bilalian and offered it as a name for all African Americans, not just Black Muslims.

As Precious Rasheeda Muhammad and Mahasin Abuwi Aleem have eloquently described, he offered the name to Black Americans in light of our historical search for “a dignified name.” He preferred the term “Bilalian” over “black” and selected it as the name for African Americans: “I think there’s more dignity in identifying with an ancient ancestor than in identifying with skin color. When I say I am a Bilalian, I’m saying that I am a man like Bilal.” He chose Bilal, companion of the Prophet Muhammad emancipated from slavery after embracing Islam, because he was the Muslim ancestor whose story most reflected the narrative of African Americans.

Ana Karim states, “The Imam had told us Bilal is a prototype of us. . . .His enslavement did not break his will. He held fast to Almighty God. So, the imam said, ‘We are [now] the prototype; we are Bilalians.’ The Imam wanted us to be a beacon or harbinger to the future generations to reach for excellence.” The Bilalian News (later changed to Muslim Journal) was an offering, inspired by the Muslim tradition, to all Black Americans.* Ana continues:

Bilalian News stood on the shoulders of Muhammad Speaks in that the Honorable Elijah Muhammad said in Muhammad Speaks, “Up you mighty Nation, you can accomplish what you will.” Imam W. D. Mohammed, by naming it Bilalian News, he was saying to our people, “You have the wherewithal within you, God has put all the ingredients in you, to become a great people and become respected by the world. . . .He was reaching out to our people to strive for human excellence.

My recognition as a young faith leader by a Black magazine is simply one of the many fruits of the efforts of Imam W. D. Mohammed and his early followers, including my parents. Because Imam Mohammed loved his people and dedicated his community’s newspaper to Black Americans at large, it is no surprise that we are now recognized by one of the most important magazines in the history of the Black freedom struggle.

Indeed, I associate JET with my Granny and Grandpapa, Mrs. Lavada Smith and Dr. Harvey Smith, who always had a copy of the magazine on their coffee table. It was hard for my Granny when my father became a Black Muslim, but over time, as her grandchildren grew with character and intellect, she began to see the beauty of the new life my father had chosen. Her seeing me in JET as a faith leader in the Black community would have sealed her appreciation for Islam, I like to imagine. I am blessed that my 91 year old grandfather has lived to see this day.

May our sons and daughters bring greater light and clarity on a faith meant to benefit all of humanity.

* Bilalian News included a statement of its “policy objectives.” The first five were: “1. Advancement of the moral, and educational development of the entire society. 2. Encourage support for the financial development of economically deprived communities in the society. 3. The presentation to the world of the religious mission of the World Community of Islam in the West, and its community building activities. 4. The presentation of positive Bilalian achievements within and without the United States. 5. The censuring of destructive and negative influences which have traditionally impeded Bilalian development.” “Bilalian News Statement of Policy,” Bilalian News, August 26, 1977, 2.