We hear a lot today about “stand your ground” laws that are legislated in 25 states. The Trayvon Martin case in 2012 gave this law wide media attention. Since then, there have been several other controversial stand your ground cases. Most recently, Markeis McGlockton, a black man, was killed in Florida by Michael Drejka, a white man, over a dispute about a handicapped parking space. Drejka has since been charged with manslaughter.

While the specifics of stand your ground laws vary from state to state, the basic tenet of the strongest legislation (in Florida), is that if you feel threatened (i.e. you believe you are in imminent danger), you do not have to “retreat” from the situation, but rather you can act in self-defense, including using deadly force.

There are myriad reasons why someone might feel “threatened”, and advocates for repealing these laws point to deep-seated racial stereotypes, especially that black men in general pose a “threat” to society. We only need to look at the mass incarceration rates of black men and the disproportionate number of cases where they are later (usually much later!) exonerated to know that this presumption of danger is false and has massive implications. Black men constitute 47% of the 1,900 exonerations listed in the National Registry of Exonerations (as of October 2016).

Stand your ground laws are indeed troubling and disproportionately impact black people, but I want to take a different spin on the concept. Before I do, I must offer a key disclaimer. I am a pacifist—against violence of any kind—and I am particularly anti-gun. So, the commentary to follow should be read and interpreted metaphorically.

What if black people (or other marginalized groups) could stand their ground when they felt their identity was being threatened—when they felt the very core of their being was in imminent danger of being “killed”? What might “stand your ground” look like if there was a law for marginalized people that gave you the right to challenge the system that “kills” you and not be met with defensiveness or downright dismissals of your assertions? What if you would not be “arrested” (e.g. perceived as overly sensitive, angry, written off as having no potential for upward mobility in the organization, put on a performance improvement plan, labeled as not being a team player, etc.) if you stood your ground by calling out the inequities that hurt, demean and eventually kill your spirit?

What if black people (or other marginalized groups) could stand their ground when they felt their identity was being threatened—when they felt the very core of their being was in imminent danger of being “killed”? Share on XAs Robin DiAngelo points out in her book White Fragility: Why It is so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, a deeply entrenched racist system protects white people from having to address the inequities that black people and other marginalized groups face. The system does not allow black people to stand their ground for fear of being accused of “calling the race card”. The ramifications of standing your ground in the workplace can be dire figuratively and maybe even literally. Standing your ground can kill your chances of ever being seen as equal and deserving, and in extreme cases, the stress and trauma can cause physical health problems that lead to an early death.

DiAngelo points out that white fragility shuts down any meaningful dialogue about these systems because white people tend to be so uncomfortable with the discussion that the responses range from outrage (“Why are we having this discussion—race has nothing to do with it!”) to tears (“I am so emotionally upset that you would suggest that I am racist that I am moved to tears”).

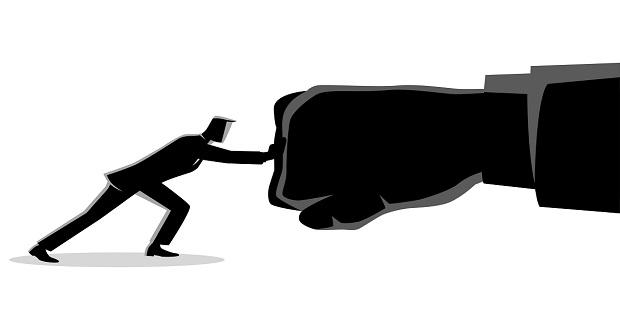

If marginalized individuals could stand their ground, dominant groups would have to take the “blow”. It might feel like you have just been “shot”. It hurts. You are being accused of something that you are not guilty of. It is not your fault. Such a “blow” surfaces a lot of emotions that don’t feel good. It makes you uncomfortable. Allowing black people to stand their ground often requires that white people lean into the discomfort of their own feelings of guilt, fear, anger, and resentment.

However, unlike the literal stand your ground fatalities, healing is possible in my version of this “law”. Healing comes with choosing not to take the “blow” personally, even though it feels personal. Racism is a system of injustices, and we are all a part of the system, either as victims or complicit sustainers of it. Healing comes by gaining more understanding of how the system hurts black people and other marginalized groups. Healing comes by learning to empathize rather than merely sympathize.

Let marginalized people stand their ground. Do not deny, interrupt, dismiss or minimize our experiences. Listen to our stories. Commit to understanding how the world operates differently for us. Accept that our life’s experiences are very different from those in the dominant group. It may not be your fault, but if you are not willing to listen and understand, you do become a part of the systemic problem.

It may not be your fault, but if you are not willing to listen and understand, you do become a part of the systemic problem. Share on X