Two weeks ago I was asked to participate on a wonderful panel discussion about the iconic status of Martin Luther King, Jr. The theme of the panel was inspired by the historical fact that many black households would place images of Martin Luther King alongside images of Jesus (and JFK). This occasion compelled me to think about the general use and function of an icon and the ambivalent consequences of treating King as an icon of black freedom struggles.

When we think of the term icon, at least two related meanings come to mind. The term traditionally has religious and theological connotations. An icon is a representation of a divine or sacred figure like Jesus, the Virgin Mary, or the Buddha. For some people, the very notion of an icon blurs the line between the sacred and profane; therefore, some are suspicious about making images of divine beings and powers because these images ignore the distance between the human and divine. In addition to this more literal conception of the icon, we can think of an icon as an exemplar or representative of some cultural ideal or value (strength, beauty, generosity, courage, justice). For instance, for many people President Barack Obama is an icon of racial progress; whether they agree with his politics or not, people see him as a signifier, and embodiment, of America’s commitment to racial freedom and equality. To some extent, both notions of the icon come together in Martin Luther King. He has become a cultural hero with a holiday and memorial on the National Mall; he has become an available symbol of courage and hope for both liberals and conservatives. At the same time, King has attained sacred status for some people. In other words, King’s image is treated as if it was transcendent, exceptional, and pristine. This explains why people get nervous when discussions about King’s personal and political flaws get underscored. It explains why leaders like Al Sharpton indirectly use their affiliations with King to authorize their voices and claims (as if King’s speeches and ideas were unquestionable sources of authority and guidance).

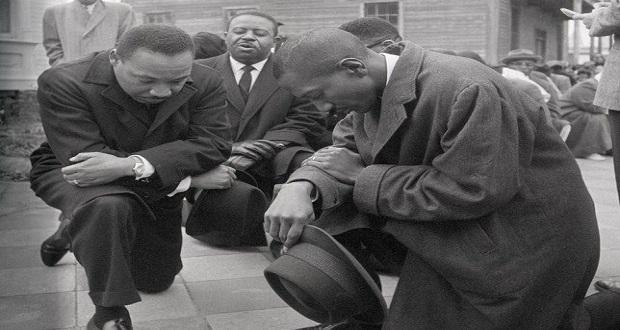

Perhaps we cannot live without cultural and political icons. Icons inspire, galvanize, and provide rallying points for communities. Images of freedom fighters such as Ida B Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Malcolm X, and MLK also provide sites of memory, enabling us to connect the evanescent present and the past. Yet the production of iconic figures also hinders and blinds us. We tend to uncritically revere and “worship” iconic leaders without interrogating the complexities, tensions, and failures of their visions and practices. In addition, images of the “individual leader” tend to conceal the broader contexts, forces, and communities that produce leaders. Finally, the process of becoming a national icon necessarily ignores the qualities of that person that were subversive and resistant to national projects and agendas such as war and militarism. In the specific case of treating King as an icon, we forget visions of black freedom that conflicted with King’s more acceptable aspirations; we forget the everyday men and women that contributed to the struggles in the 50s and 60s; we forget that King experienced doubts, depression, melancholy, and so forth. While a general attachment to icons is second nature to human beings, we should be mindful of what iconic attachments prevent us from seeing and imagining.