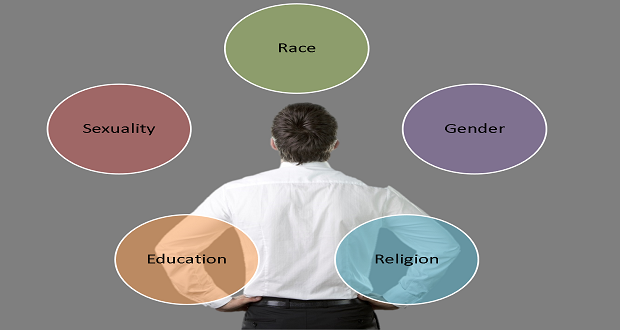

One of my favorite exercises The Winters Group uses in training groups on cross cultural competency is an activity in which we ask participants to think about the groups (organizations, institutions, identity groups) that have most deeply shaped who they are. The silence that comes over the room as individuals try to rank these “outside” factors is always interesting. You can almost hear people struggling to decide, “does my gender shape me more than my race?” or “does my religion shape me more than my sexuality?” or “is being a parent more influential than my education?”

This activity is difficult, and effective, for a reason; namely because we rarely think of our individual personalities as the result of things largely out of our control. Our culture strongly emphasizes, and in some ways idolizes, a very psychological view of the self and personality. We say about ourselves, “I’ve just always been that way” or about others, “they’re just that type of person.” Statements like these assume that people are unique from birth and leave the reason for their peculiarity unanswered. The truth is, all of our unique personality traits came from somewhere. They are the result of being born into various family sizes, economic situations, skin colors, body shapes, religions, specific places on the map, etc.

Another reason I am particularly drawn to this activity is because it is a very practical application of foundational elements of sociology. In the 6 years I have been teaching sociology, I have spent the bulk of classroom time doing very similar exercises and illustrations. In fact, my main goal at the end of each course is that students have a deep grasp on how they have been shaped by the world around them.

I also have a renewed appreciation for this exercise because of how helpful I have seen it as I have counseled some of my closest friends with their own work life issues. I want to share just one example. I have friend who is very successful in the medical field. She is a young, second generation Jamaican who was educated at a very prestigious university. She was recently asked to train a much older white male from the American South. Their interactions started out great but have eventually led to several heated confrontations that have involved their superiors. The confrontations largely involved failed attempts at humor, misunderstood social cues, ambiguous seniority, and disagreements about various styles of job performance.

As I listened to my friend tell me about her frustrations in dealing with her colleague, I was struck by how much language was used that focused on each individual. “That’s just not my personality”, “He’s just that type of person” and “our personalities just clash.” After some time of listening to the details of their confrontations, I began to ask her about what social factors she thought might be coming into play and I could sense some relief as she began to list off several factors that could be shaping their interactions. I challenged her to think about the dynamics of their respective ages, race, cultures, religion, and education and how they may be influencing their “personalities” and confrontations.

Despite their very heated confrontations, I think my friend and her colleague both share a genuine desire to understand each other and create a more enjoyable work environment. What was missing in their assessment, and subsequent lack of resolve, of their conflict was a focus on what outside factors were framing their interaction. Turning one’s focus from the minute point of personality to the larger forces that shape them has several advantages. First, it is easier to demonize someone, and further your frustration, when your explanation for conflict is solely based on their unmoving personality. Second, thinking about factors larger than the individual is a way to start towards a workable solution and deeper understanding of the situation. Lastly, there is some relief to both parties when the “blame” can be shifted away from themselves and towards some larger social factor. And a resolution to conflict is much easier to achieve when both people are approaching a situation from a place of reasoned control, and not passionate emotional reactions.