I consider myself somewhat of a movie buff so I do my best to take advantage of the winter months to see as many films as possible—to both escape the cold and enjoy the higher quality films that the season brings. There are two movies out now that I want to recommend to you as living-lessons on organizational life and morality: Spotlight and The Big Short. Both films are not only well done and entertaining, but they are incisive cultural critiques based on true events in American culture. Although much could be said about each film respectively, I want to briefly describe several lessons that the films teach us (with as few spoilers as possible) about how organizations act as both the script and the stage for being ethical people in modern workplaces.

Without going into detail on the various plots, characters, and conflicts in both films, I want to highlight how each pull back the curtains of how organizations and industries work to shape our ethical choices for both good and evil. In Spotlight, the organization is the Catholic Church—globally and in Boston—and the story is how a team of journalists uncovered the now infamous child molestation scandals that at one time garnered global attention and outrage. In The Big Short, the organizational landscape is the banking industry and covers the national housing crisis and its subsequent global impact by following the quirky group of investors who saw the crash coming before anyone else—and capitalized on it. Although both films are dealing with very different topics–and widely different establishments—it is their treatment of large organizations that make them worthy of comparison. This is especially true if you think about the role that each organization played in shaping the decisions of both bankers and priests in their respective scandals.

A focus on the role that organizations play in shaping morality, ethics, and manifestations of good and evil is especially important for a culture like the American culture whose individualism is much more savvy at pointing the blame at particular individuals—and rarely at particular industries or organizations. By no means do I want to suggest that the specific individuals—bankers and priests—who were responsible for such wide scale pain should be looked at more generously or be held to a lower standard of accountability. But I do think it’s important that we do the much harder work of thinking about the organizational cultures and contexts that may have produced such monsters.

The films do a nice job of painting a complex picture of the perpetrators and the myriad of bystanders who played supporting roles in the grand scheme of things. In The Big Short, you meet seemingly harmless—and even charming—bankers who can escape the weight of their ethical choices by hiding behind the complexities of the financial market. It is much easier to manipulate numbers from a computer screen than to physically evict a family with small children from their defaulted home. In Spotlight, you meet committed Catholic parents, teachers, priests and who replace a concern for the victims of sexual violence with a concern for the “greater good” and spiritual well-being of a religious organization and community. The explicitly corrupt bankers and priests who were found guilty are easy to deal with; it is the supporting cast and organizational cultures that seem to be let off the hook and fade into the background. As it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to destroy one (I think that’s a quote from Spotlight).

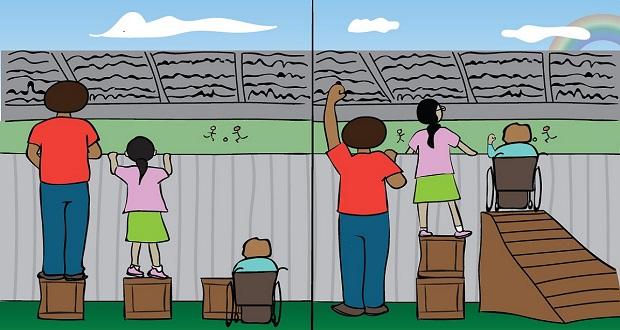

I don’t want to give too much more away because I hope you’ll see the films for yourselves and come to your own conclusions. But the films taught me an important lesson about the vital role that organizational cultures play in shaping the world—for both good and evil. We are more accustomed to thinking about organizational culture as a driver of productivity and innovation, but what about for morality, ethics, spiritual vitality, and expressions of evil? When we see incidents of inequality in the workplace for example, do we immediately seek to isolate—and eliminate–the individuals involved or will we also consider the many policies and people along the way who played a supporting role in creating the situation from the beginning? These are tough questions with even tougher answers, but lasting cultural change and the moral character of an organization is at stake when we try to simply convict the villain while ignoring the village.

![A Point of View: Chief Diversity Officer Role Not Looking So Bright [INFOGRAPHIC]](https://theinclusionsolution.me/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/CDO-of-the-Future-Infographic-620x330.png)