In many workplaces today, the following situations are not uncommon: an assertive female manager may be labeled “a bit*h” while the same behavior lends her male counterpart the description of an “effective leader”; a gay person may avoid displaying a picture of themselves with their partner or spouse because it may be perceived as “flaunting” their sexuality; or an Asian American employee, born and raised in the United States, may be complimented for speaking “good English.”

Statements like these that offend or make individuals uncomfortable are called microaggressions. In the book, Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact (Sue, 2010), microaggressions are defined as “everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership.” Invariably, these comments carry a “hidden” message that demeans their recipients, makes them feel they are lesser beings, suggests they don’t belong, and even relegates them to an inferior status. Perpetrators are usually unaware of the “hidden” message that is being delivered. In the examples I shared above, the messages are: that women should be passive and allow men to be the decision makers; homosexual displays of affection are considered abnormal and offensive and, therefore, should be kept private; and Asian Americans are perpetual foreigners, even in their own country.

The impact of microaggressions in the workplace

Microaggressions are indeed common occurrences in the workplace. In the recent Women in the Workplace report from LeanIn.Org and McKinsey & Co, the authors highlighted the gender-based microaggressions women are still facing. Results showed that 64 percent of the women indicated having experienced microaggressions. Women frequently have to provide more evidence of their competence than men, and often have their judgment questioned even in their area of expertise. They are also twice as likely than men to be mistaken for someone in a more junior position. Black women are dealing with a greater variety of microaggressions and a larger number of them indicated having their judgment questioned in their area of expertise. They also indicated being asked to provide additional evidence of their competence. Results were even more alarming for Lesbian women: 71 percent of them indicated having been the recipient of microaggressions. In fact, lesbian women are far more likely than other women to hear demeaning remarks in the workplace about themselves or others like them. They are also far more likely to feel like they cannot talk about their personal lives at work.

Women frequently have to provide more evidence of their competence than men, and often have their judgment questioned even in their area of expertise. Share on XFor many marginalized groups, addressing microaggressions puts them in a “catch-22” situation. If they do nothing, they end up suffering from a sense of low self-esteem, a feeling of not being true to their self, and a loss of self-integrity. Yet, to confront the perpetrator may result in negative consequences. The sad reality is that most marginalized individuals choose to do nothing, especially if there is a power differential between perpetrators and their targets. It is not uncommon for those on the receiving end of insults or offensive remarks to be asked to “let it go” or “get over it”; after all, the comment was “innocent” and made with “no-harm intended.” These expectations only serve to deny the harmful impact of the inflicted biases.

The impact of microaggressions in the workplace is devastating for all concerned. When left unaddressed, they enforce marginalization, deny equal access to opportunities, and invalidate the way oppressed groups experience their own reality. Because most individuals see themselves as good, moral, and decent human beings, acknowledging their own biases and discriminatory practices will, most certainly, contradict the way they see themselves. Consequently, they avoid discussing their microaggressions, which, in turn, only serves to discourage others from addressing the same issues.

The impact of microaggressions in the workplace is devastating for all concerned. When left unaddressed, they enforce marginalization, deny equal access to opportunities Share on XThe end result: it preserves the self-image and innocence of the oppressor, silences the voices of the oppressed and, most troublesome, it prevents existing inequities from being addressed. While anyone can be on the receiving end of disrespectful behavior, microaggressions are more often directed at those with less power, such as women, people of color, and LGBTQ people.

Concluding Thoughts

While many of us truly believe that we are nonprejudiced, hold egalitarian values, and would never deliberately discriminate, the reality is that we all harbor unconscious biases that, if unchecked, can result in discriminatory actions.

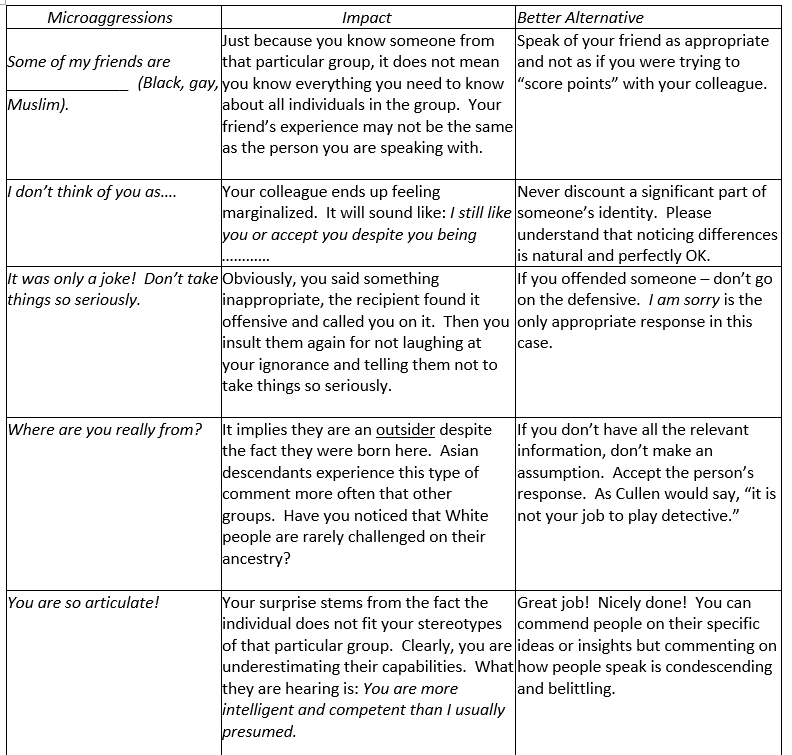

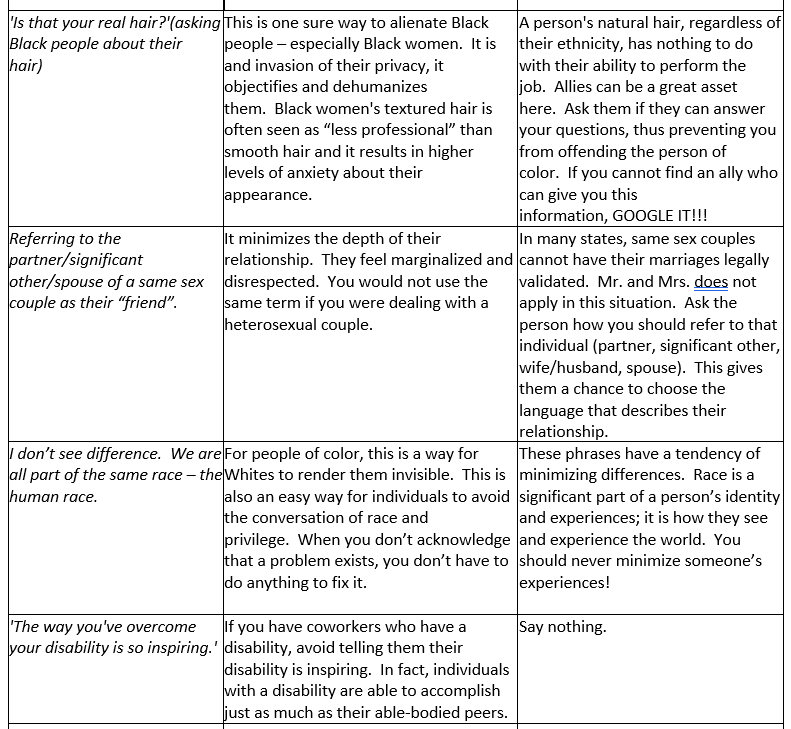

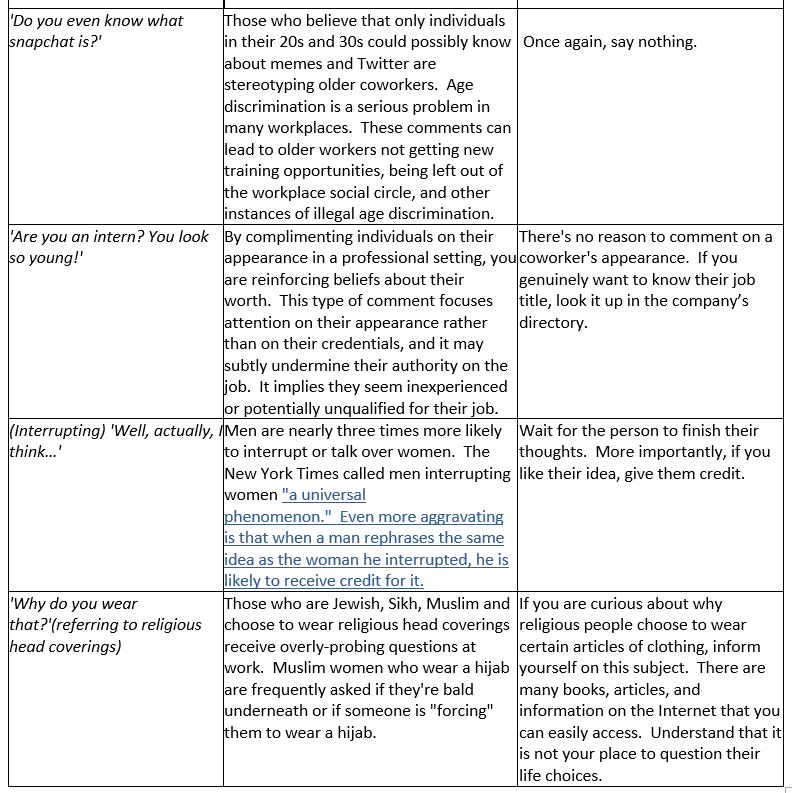

Below, you will find a list of common microaggressions compiled from Maura Cullen’s book, 35 Dumb Things Well-Intended People Say, and from Rachel Premack’s article in the Business Insider titled, “14 Things People Think Are Fine to Say at Work, But Are Actually Racist, Sexist, or Offensive.” I would urge you to understand the impact they carry and consider adopting their more inclusive, less offensive alternatives.