Analyzing data and interrogating data are not the same thing. We currently analyze diversity data, but we less often interrogate it with a justice lens. Last week, Brittany J. Harris defined justice as the “presence of systems and supports (policies, practices, norms) that achieve and sustain fair treatment, equitable opportunities and outcomes for people of all races. History and research tells us that we have yet to achieve fairness and equity in the workplace. BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) and women are still underrepresented in leadership levels — and overall underrepresented in some industries such as tech. Several studies report that BIPOC and women continue to experience microaggressions and BIPOC specifically say that they must be “on guard” at work. Company norms like “executive presence” elude BIPOC because these unwritten, arbitrarily set standards are based on white supremacist ideology. Women and BIPOC are also more likely to leave organizations due to unjust treatment.

Analysis can uncover some of these inequities, but interrogation reveals the systems that perpetuate them.

Analysis can uncover some of these inequities, but interrogation reveals the systems that perpetuate them. Share on XThis week I will explore how to interrogate internal data such as applicant flow, hiring, termination (both voluntary and involuntary), promotion, and performance appraisals.

Applicant flow:

Where do you source? How have your sourcing patterns changed to achieve equitable representation? Who manages the sourcing? What is their level of cultural competence? Who applies? Who does not apply? Where do you recruit? How has that changed over the years? How much do you rely on employee referrals? What is your applicant flow to hire ratio? These are all questions to begin interrogating your hiring processes. If your answers do not include Black talent pools or take into account Black cultural patterns or experiences, then your system might be perpetuating racism.

The Winters Group conducted a cultural audit for a client a few years ago. This client had a goal of improving women in leadership. During our analysis period they had 100 openings that they filled with external candidates. Women had applied at the same rate as men, however, only one woman was hired out of the 100 open positions. This is where the interrogation begins. Why was that the outcome if there was a stated goal to improve the representation of women? We recommended that the company review every resume received, as well as interview notes to understand this outcome. It is a reverse engineering of sorts — backtrack to understand what happened in the system that caused that result.

Hires:

Who did you hire? Why? In what ways did your hiring profile align more with cultural patterns and characteristics associated with whiteness? For example, how often do hiring managers use “good fit” for the final decision?

Who did you hire? Why? In what ways did your hiring profile align more with cultural patterns and characteristics associated with whiteness? How often do hiring managers use 'good fit' for the final decision? Share on XLauren Rivera, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management conducted research that revealed that hiring is as much about cultural matching between candidates, evaluators, and firms as it is about skills. In her research, employers hired candidates who were not only competent but also culturally similar to themselves in terms of leisure pursuits, experiences, and self-presentation styles. Leveraging a justice lens means organizations should dismantle these subjective criteria by interrogating what hiring managers really mean by “fit” and disrupting processes that allow for those biases to be used.

The Winters Group also looks at 5-year projections for hiring of BIPOC and other historically underrepresented groups to allow for matching of stated goals and likelihood of achieving those goals at current and historical rates. HR business partners often lament that they bring candidates of color to hiring managers but often they are not the selected candidate. Perhaps HR needs more power in the final decisions. Perhaps final decision making should not be in the hands of one person (or people who identify in similar ways).

Promotions:

Some very large Fortune 500 companies that we have conducted audits for, do not maintain reliable data on promotions. They change job codes or have inconsistent titling of jobs making it difficult to analyze promotions data. Organizations should develop reliable promotions data. The excuse that “our data is not in order,” is a form injustice in and of itself.

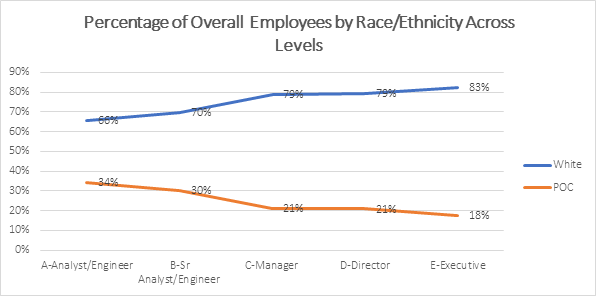

Some very large Fortune 500 companies do not maintain reliable data on promotions. The excuse that “our data is not in order,” is a form injustice in and of itself. Share on XFor those organizations where we can examine promotion history and projections, it often reveals concrete ceiling and sticky floors. The graph below is a client example that shows that white people’s trajectory for leadership increases from the entry level analyst position while the opposite is true for BIPOC. Interrogation should include examining every single promotion, who was considered, and rationale for the decision. In addition, companies that have “ready now” (those individuals ready for a promotion) practices to manage career advancement should examine the diversity of those who are deemed “ready” for a promotion and importantly, who is not ready and why not.

Performance Reviews:

BIPOC often are disproportionately rated lower than their white counterparts. Studies show that Black employees are over scrutinized and penalized more severely for mistakes. People managers should be required to defend these disparities based on unbiased criteria. In addition, correlations between performance and promotions should be analyzed. We have found that there is not always a correlation.

BIPOC often express that they do not receive straight forward feedback and thus are unable to adjust performance. BIPOC should be more diligent in requiring specific feedback from leaders with questions like, “Can you give me a specific example of that? Or “Specifically what behaviors would draw you to that conclusion?”

Terminations:

Many organizations that we have conducted audits for are woefully lacking in the data that they collect on why people terminate voluntarily. Multiple choice categories such as “return to school,” a better opportunity,” or “family reasons,” are common. Applying a justice approach should include a qualitative exit interview that probes in depth about the leaving employee’s experience around issues of equity and justice. In our audits, we often find that BIPOC are terminated involuntarily at disproportionate rates. Again, the reason codes do not provide the whole story — “poor performance,” “violation of the rules,” and “misconduct” are popular categories. To understand the disparities, we need to interrogate what is happening in the system that creates this outcome. Below is an example of a five-year projection for involuntary terminations at this company. How will they stem the tide if they do not get to the root of the issue?

A justice approach should include a qualitative exit interview that probes in depth about the leaving employee’s experience around issues of equity and justice. Share on X

Intersectional Data Analysis:

It is important to recognize intersectionality in our interrogation. How do the experiences of Black women differ from those of white women, for example? Research shows that the experiences are very different. Black women receive less support and mentoring than other groups. How do the experiences of Millennials of color differ from their white counterparts? How do the experiences of Black engineers differ from Black maintenance workers? These deeper analyses are not always possible because the numbers are just too small. This is also where collecting qualitative data analysis can provide the robust insights where quantitative analysis may be limited. We’ll explore this in a subsequent post.

Analyzing data brings potential inequities and injustices to the surface. Interrogation uncovers practices and policies that cause unintentional harm and disadvantage BIPOC and other historically marginalized groups.

Analyzing data brings potential inequities and injustices to the surface. Interrogation uncovers practices and policies that cause unintentional harm and disadvantage BIPOC and other historically marginalized groups. Share on X