This is the second in a series of articles on what it means to have bold conversations about race.

As I mentioned last week The Winters Group is sponsoring a new feature at The Forum on Workplace Inclusion called Bold Conversations: Calling the Race Card. I started the series last week asking, are we ready to have bold conversations about race? I would suggest that many of us are not because we do not have the skills or the tools to do so. We have been asking people for years to sit down and talk about our racial divide. However, as we have witnessed from the rash of racially implicated incidents over the past few years, we are not doing a very good job in improving race relations and some might say that we are regressing. Before we lay out some tools and skills, it is critical to define what we mean by race.

The definition of race is an evolving one. Today, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the definition used to classify people is based on the notion that race is not “scientific or anthropological” and takes into account “social and cultural characteristics as well as ancestry”, using “appropriate scientific methodologies” that are not “primarily biological or genetic in reference.” The race categories include both “racial and national-origin groups.”

While recent research on race proves that race is a social construct with virtually no biological basis, we know that race still matters a lot.

A few years ago The Washington Post did a piece called, Role of race reemerges in DNA-testing debate. One of the contributors to the article said, “We recognize that race is a ‘fuzzy concept’.” “Fuzzy” as it might be, it continues to be a divisive, complex topic fraught with painful memories and daily reminders for many. And for others, race is an issue that they want to bury once and for all either because it is just too uncomfortable to talk about or they want to believe that we live in a “post-racial society” where we are all treated equally.

While the anthropological definition, which was accepted until recent years that laid out three races including Caucasoid (of European descent), Mongoloid (of Asian Descent) and Negroid (of African descent), might be outmoded, we know that visible physical characteristics continue to result in disparate treatment for certain groups.

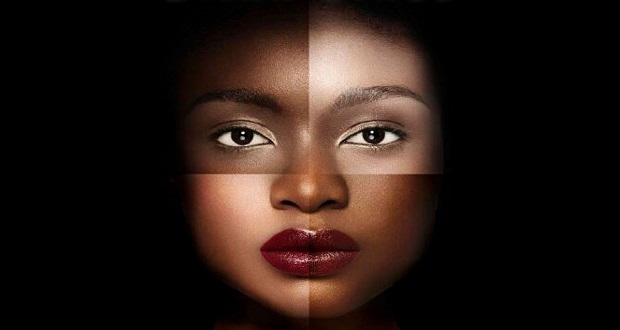

For the purposes of the Bold Conversations, I want to focus on race as it relates to the physical characteristic of color. There is a great deal of evidence that the color of one’s skin determines how fairly and equally they are treated. As a matter of fact, globally, the darker one’s skin tone, the more likely they will receive disparate treatment. A phenomena known as colorism, it is the source of bias, prejudice and racism.

I conclude that it is color that matters more than race. We will explore the ramifications of colorism in greater depth in the next post.