“The most disrespected person in America is the black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the black woman. The most neglected person in America is the black woman.” Malcolm X quoted these words in 1962. As a Black woman, I would suggest they still resonate today. There is no shortage of data points, studies, or anecdotal observations that substantiate the ways in which Black women continue to experience the compounding effects of racism and sexism in their workplaces, communities, and daily lives.

Whether it’s experiencing persistent pay inequities all the while maintaining the role as ‘breadwinners’ and primary caretakers for our families; being at greater risk for maternal mortality and disparities in healthcare—despite how much you think ‘you’ve made it’ up the socioeconomic ladder; navigating the daily microaggressions in the workplace that suggest all of who we are might be too much or not enough; or the sickening reality that even in our youth, we’re seen as less innocent, less deserving of protection and care—one would be hard pressed not to find some truth in Malcolm X’s quote. For those reasons, alone, I’d venture to say that Black women have quite a bit to be angry about.

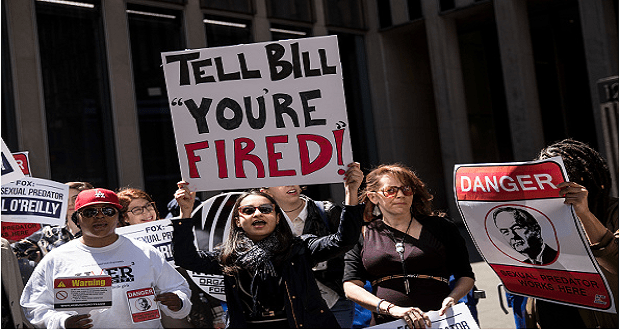

Yet, the “Angry Black Woman” narrative is often used to stigmatize and undermine black women who choose to challenge the racism and sexism they experience, or who dare to affirm what they deserve. Share on XYet, and still, the “Angry Black Woman” narrative is one that is often used to stigmatize and undermine black women who choose to challenge the racism and sexism they experience, or who dare to affirm who they are and what they deserve. The “Angry Black Woman” narrative essentially characterizes Black women’s anger as irrational, uncalled for, an overaction, and a deviation from what is required to be seemingly ‘respectable’—particularly in the eyes of white people. Black women must ‘take the high road’—or more eloquently put, ‘go high’ even when ‘they’ go low. We are enculturated to suppress our true, authentic feelings out of fear or risk of disturbing the comfortability of white people. This dynamic in and of itself is a form of oppression—one that I too, have experienced and even internalized.

The “Angry Black Woman” narrative essentially characterizes Black women’s anger as irrational, uncalled for, an overaction, and a deviation from what is required to be seemingly ‘respectable’—particularly in the eyes of white… Share on XIn those environments where I was the ‘only,’ I struggled with balancing what it meant to advocate for myself in a context where that advocacy could be misinterpreted as confrontational or invalid. “Brittany, If you speak up for yourself, they may think you’re being radical. It’s not worth it.” I recall learning to adapt my direct and expressive communication style as a survival (thriving) mechanism to avoid being interpreted as ‘sassy,’ aggressive or intimidating. “Brittany, you don’t want them to think you’re ghetto or unprofessional—you’re a different kinda black.”

When experiencing the ever present, ‘papercut-like’ nature of racial microaggressions, I remember feeling choked up, yet resisting the urge to share my truth or engage out of fear of making them [white people] feel bad. “Brittany, they probably didn’t mean it that way. If you share how you feel, they might get it offended.” And even today, when I find myself engaged in dialogue around sexism and misogyny within the Black community, there’s sometimes this subtle expectation to prioritize blackness over womaness—to subdue my truth, feelings, and pain in service of a much greater ‘cause.’ “Brittany, don’t be too critical of our own. It doesn’t help our community.”

What’s so wrong with being an Angry Black Woman? Anger is a very real and valid feeling. It is (or should be) an acceptable response to mistreatment and discrimination. Share on XI find it fascinating how I’ve essentially learned (internalized) that suppressing my feelings, truth, and anger (despite how much studies show this can be a detriment to my health) is worth not being characterized as or associated with being an “Angry Black Woman.” What’s so wrong with being an Angry Black Woman? Anger is a very real and valid feeling. It is (or should be) an acceptable response to mistreatment and discrimination. It has been proven to be a powerful channel for action, change, and impact. Angry Black Women disrupt and dismantle systems. Angry Black Women affirm their truth and amplify the experiences and truths of others. Angry Black Women show up and do the work—all the while living through and managing the toll of the trauma and pain they experience. Angry Black Women are Strong Black Women—and that is a narrative I strive to reconcile and internalize every day.

Angry Black Women are Strong Black Women—and that is a narrative I strive to reconcile and internalize every day. Share on X

Editor’s note: The Winters Group created a reflection guide on this Inclusion Solution series. The purpose of this guide is to revisit the perspectives shared and to encourage greater self-reflection and critical thinking about the ways this topic influences your world. Also included in this guide are activities and reflection questions for you to engage in as you begin your journey. Download the guide here.