“White Fragility?… Hmph. Must be nice.”

I must admit, my initial reaction to learning this term sounded a little bit like that. My reaction was grounded in some curiosity, but mostly skepticism and perhaps even a little annoyance. I was fascinated by how even a term that was meant to be “critical” to some extent, still could elicit a certain degree of empathy, understanding, and maybe even pity. The word ‘fragility,’ and its root word ‘fragile’, is often associated with the need to be “careful” or “gentle” with a subject. It suggests a certain degree of delicacy; thereby requiring more effort in handling whatever or whomever it is. When something is “fragile,” you may be expected to do a little more work to make sure the object at hand remains “intact” or “safe.”

These were terms and qualifiers that came to mind for me when I first heard the term ‘white fragility.’ These are also conditions (e.g. safety, care, being gentle) that many black people (and people of color) are not afforded when sharing their truths and experiences around race—particularly when engaging with their white counterparts. I share this not to be critical of Robin DiAngelo’s use of the term, but rather to acknowledge the way in which power and privilege can even influence our framing, language and whom we deem worthy of the benefit of the doubt… or “extra care.”

Power and privilege can even influence our framing, language and whom we deem worthy of the benefit of the doubt… or “extra care.” Share on XI think about the term “race card,” for example. This term has traditionally been used in response to a black person sharing the ways in which race has influenced their experience. The “race card” typically suggests skepticism or an assumption that one may be exaggerating their experience—both of which can ultimately undermine or invalidate one’s truth. I think we could agree that experiencing skepticism doesn’t feel the same as being regarded with “care”.

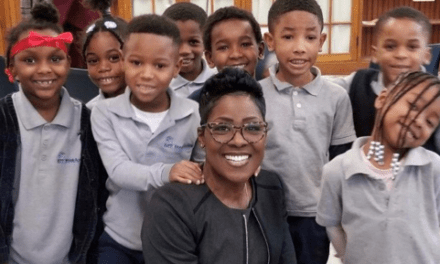

Nonetheless, DiAngelo’s work is certainly compelling, and a necessary affirmation of what many black people (and other people of color) have experienced but couldn’t quite name when engaging in dialogue around race and diversity with white people, even as early as childhood. As a matter of fact, I was recently at a curriculum advisory board meeting for an urban school district. At this meeting, the board chose to engage a student, a black girl in the 7th grade, in the curriculum review to provide feedback as a student. (For context, the curriculum is centered around identity and understanding complex topics like race and systems.)

When asked her thoughts and what she would recommend, the student offered what I thought was an astounding response and youthful articulation of the burden of white fragility—a burden that many black people are expected to bear. She wanted us to make sure that when they experienced the assignments and discussed the articles (one of which explored the impact of redlining, gentrification, and modern-day segregation in urban cities) that “the teachers not make the few white students in the class feel badly about their ancestors.” She added that she didn’t want the white students to “be sad or get offended.” She referenced a previous experience in class where the teacher had to pause the class discussion to “help them [the white students] feel better,” which took away from the bigger group’s time to talk about “solutions or how they, as students, could build a better city.”

In her own way, this young girl was explaining white fragility—and the ways in which it showed up in her world. She was beautifully articulating how, even in her youth and innocence, she had to be mindful of her white counterparts’ feelings and take “extra care” when discussing the ways in which her community continues to be impacted by systemic racism. How powerful, I thought, that in that moment—in that room with teachers, curriculum designers and other board members (people in power)—this black student studying within an urban, underfunded school system, living within a socioeconomically, disenfranchised community, still felt compelled to center the feelings of white students when sharing what she wanted to see in the curriculum—a curriculum designed to honor and affirm her identity and truth.

Wow.

This dynamic is something I’ve experienced, perpetuated, and become more intentional about acknowledging when facilitating dialogue or sessions on race. We should be asking ourselves, which groups experience power and which groups do not? Who has traditionally been affirmed and heard, and who has not? Why might engaging fully and authentically be more difficult for some over others? In what ways might my intention to “meet some people where they are” undermine the truth and experiences of others?

In our work at The Winters Group, we emphasize taking a developmental approach to learning and education—meeting people where they are in their journeys. This means being aware of and naming the ways in which our identities influence our understanding of and readiness to discuss race. This also means knowing that white fragility is real and understanding how to adapt and reframe content to create shared meaning. AND… it means creating spaces where we are affording people of color the “safety” and “extra care” we afford white people when they choose to share their truths and experiences around race. It means putting norms and mechanisms in place to relieve them of the burden of white fragility.

Meeting people where they are in conversations about race means creating spaces where we are affording people of color the “safety” & “extra care” we afford white people when they choose to share their truths & experiences Share on X