As children, many of us feared the monsters under our beds or lingering in our closets. Some of us sought nightlights for refuge from the dark, many found ease in shutting our closet doors tightly, and others ensured they were tucked away, hidden under the covers.

I, for one, believed that the covers on my bed would shield me from the evils that might be lurking in my room. One thing that kept me vigilant in my attachment to the covers was knowing that the mere slip of a limb exposed from the cover would leave me vulnerable to a monster in the night.

As we age, the mythical monsters under the bed are replaced by more tangible threats. Our classrooms, and then our workplaces, are filled with various anxieties and for many of us — especially those from marginalized groups — bias, discrimination, and othering present daily threats.

As early as 4 years old, children begin to internalize racial differences and may choose or exclude playmates based on these differences. To mitigate these experiences and keep ourselves safe from being ostracized for our differences, many of us adopt a new “cover.”

Covering is defined as minimizing or downplaying parts of one’s identity (race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability status, etc.) to conform to the dominant culture. Fast-forward from the playground to the workplace, studies have found that the majority of us do it. Some of the examples of covering below may resonate with you.

- A parent in the C-suite may need to miss a happy hour due to a PTA meeting but uses an excuse about a professional organization meeting instead.

- A gay employee may avoid joining the LGBTQ+ employee resource group to avoid being associated with the queer community.

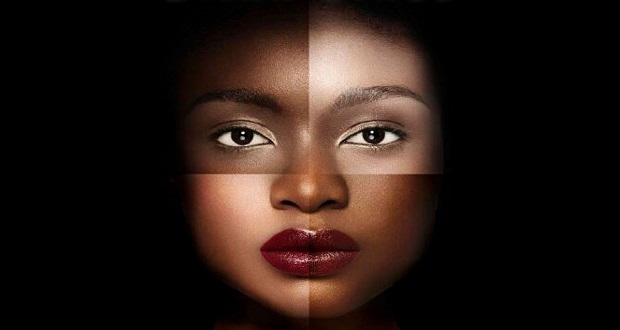

- A Black woman who otherwise sports an afro straightens her hair for a job interview.

These kinds of covering are employed to avoid experiencing bias from those around us as it pertains to elements of our identity and expression.

While the covers on our beds as children that shielded us from monsters provided us with comfort and security, covering in the workplace tends to do the opposite.

Covering in the workplace has been found to have a negative impact on employees’ overall well-being. Higher levels of exhaustion, burnout, lethargy, and dejection are seen in those who feel external pressure to cover caused by external stressors such as racism or sexism-based stress. These types of stressors can lead to a reduction in the overall quality of experience and can reduce innovation and collaboration due to the employee who is pressured to cover fearing the repercussions of showing up authentically.

To illustrate the burden of covering, I share the experience of one of my dear friends, who describes her experience of covering at work as “almost like getting into costume and character as a performer.”

This friend, whose teammates are without exception white and male, explains the level of preparation and decompression that it takes to go to and return from work each day:

- The premeditation around what she needs to wear or how she should style her hair, lest she receive uncomfortable questions about her appearance.

- The pressure to understand what is currently happening in the cultural zeitgeist of her colleagues that may come up in conversation — jokes she may not get, but laughs at anyway.

- The pressure to code-switch (change her vernacular or speaking patterns to mirror the speech of her colleagues).

These all compound. Even in the digital environment, she’s cognizant of what GIFs she uses, and tries to ensure they aren’t references to Black pop culture for concern of stereotyping from colleagues. “There’s work me, and there’s real me,” she says, as she refers to the exhaustion of having to play the role of her work self each day.

As we consider the impact of covering on our physical and psychological well-being, we must consider how to improve our workplaces to mitigate the biases, lack of belonging, and isolation people experience that lead them to cover.

The solution is not to force, or even encourage people, from under the covers when the “monster” is still under the bed. We must first acknowledge the gaps to inclusion in our workplaces.

Here are some ways to start.

Leverage Insights From Engagement and Pulse Surveys

Even if your organization does not have a formal diversity, equity, and inclusion index within your engagement survey, reviewing the trends of employee responses to questions like, “Do you feel you are part of a supportive and cohesive team?” or “Do you believe the company values align with your personal values?” may help identify themes in inclusive team dynamics or the ability to show up true to oneself.

If your organization does have a DEI index, measuring the responses to questions pertaining to belonging and authenticity against self-identified information can indicate where there are gaps for employees across different demographics, and can inform targeted interventions.

Create Psychologically Safe Community Spaces

One of the most valuable benefits of employee resource and affinity groups is that they often provide employees with a space to “let their hair down” and offer refuge from covering.

While the focus of many ERGs has shifted to focus on advancing inclusive business practices and professional development programming, it is important not to forget the value that informal networking and community building offers employees of marginalized or minoritized groups.

This is at the core of why these groups were founded, and the connections forged within these groups can be affirming and gratifying for employees who may very well not interact with others who share their identities in their day-to-day work. Hearing the stories of how their peers may have leaned into their authenticity or how they have learned to navigate various spaces cautiously but to their benefit can be invaluable to an employee’s overall feelings of belonging.

Disrupt Covering Cultures by Demonstrating Active Allyship

A tried, tested, and true set of behaviors that lead to increased workplace inclusion can be summed up by “active allyship.”

Employees can demonstrate active allyship to support inclusion by being the dissenting voice when a “joke” or remark is made targeting a particular group that may isolate employees. Taking ownership of the harm that a statement made by naming your disapproval may prevent similar statements being made in the future.

Additionally, as a manager, ensuring team engagements revolve around activities that are accessible and take the unique needs of teammates into consideration can foster inclusion.

For example, is your after-meeting happy hour inclusive of Muslim colleagues, those practicing teetotalism, or even those with a 90-minute commute home? Maybe an extended team lunch would offer the same benefits without isolating some employees.

What eventually freed us as children from the need to hide under our covers was the peace of knowing the monsters under our beds were not real. Unlike those monsters, the bias and discrimination we may experience in the workplace are very real and palpable. It will not be until we all do our part to realize inclusive spaces and behaviors that people will be free from the pressure to cover.