The Winters Group advances a model called the 4Es™ to suggest how we can become more culturally competent and better understand our “others”—those groups that we do not consider ourselves to be a part of. The first three Es are exposure, experience, and education, which lead to the ability to empathize, the fourth E.

As a part of my own education, I have been researching the differences between the “so-called conservatives” and the “so-called liberals.” I intentionally say “so-called” because some members of each group seem to be interpreting these labels in the most extreme and negative ways when considering the other group. Some conservatives characterize liberals as stupid, and some liberals believe conservatives are mean and don’t care about the downtrodden. Charles Krauthammer, a conservative political pundit who passed away earlier this year, wrote that liberals are viewed as having no head, while conservatives are labeled as having no heart.

Whenever we associate narrow and negative characterizations with any group, it exacerbates polarization and animosity, and limits curiosity and the ability to find common ground. Why would I want to know more about a group that I think (or have been led to believe) is stupid or heartless? Whatever the label, we know (well, I hope we do) that negative traits we may associate with a group are not true about all who are thought to be in that group.

A recent Pew Research Center study reports that the country’s political divisions now far exceed differences along the lines of age, education, gender, and race, and furthermore, that the share of Americans who sit in the middle of the political spectrum is lower.

In my book, We Can’t Talk About That at Work: How to Talk About Race, Religion, Politics and other Polarizing Topics (Berrett Kohler, 2017), I posit that we cannot have meaningful dialogue without common ground. I suggest that before we try to engage in Bold, Inclusive Conversations®, we need to understand ourselves and our cultural others, and create “brave spaces” where trust and common ground can be built.

. . . before we try to engage in Bold, Inclusive Conversations®, we need to understand ourselves and our cultural others, and create “brave spaces” where trust and common ground can be built. Share on XSo where is the common ground between so-called conservatives and so-called liberals? Behavioral scientists studied different political ideologies long before we became so politically polarized, and the consensus among the experts is that we share a core set of values, but they are prioritized very differently by members on either end of the political spectrum. In addition, research has shown that there are differences in brain processing between self-identified liberals and conservatives. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt draws from the work of brain scientist Gary Marcus who claims, “The initial organization of the brain does not depend that much on experience. Nature provides a first draft, which experience then revises.” He points out that innate does not mean unmalleable; but rather, “organized in advance of experience.”

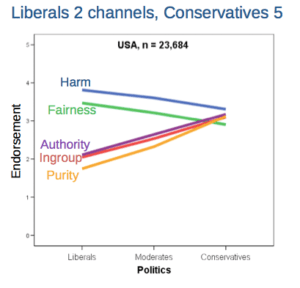

Haidt and a colleague researched anthropology and evolutionary psychology literature to better understand what they call “the moral mind.” They were looking for the sorts of values or moral ideologies that people talk about across disciplines and cultures and that, to some extent, we were born with. They found five “best” matches, which they call the five “foundations of morality.” They then constructed a global survey, to which over 23,000 people around the globe have responded. The survey can be found here. It first poses questions to measure an individual’s “openness to new experiences,” which determines one’s liberal versus conservative slant. Then, it introduces questions on the five foundations of morality.

The first universal moral foundation is harm/care. As humans, we are programmed by patterns of neural activity and our hormones to bond with others and feel compassion, especially for the weak and vulnerable. We are also wired to stay away from harm and seek safety—flight or fight. A great deal of research has shown that people become more conservative when they feel threatened and afraid. As a matter of fact, brain scans show that people who self-identify as conservative have larger and more active right amygdalas (an area of the brain that’s associated with expressing and processing fear) than self-identified liberals. This aligns with the idea that feeling afraid is associated with leaning more to the right, and that conservatives are more apt to do so. Conversely, Yale psychologists published research in 2017 that showed that, when people imagine they are completely safe from harm, they (temporarily) hold more liberal views on social issues.

The second universal moral foundation is fairness/reciprocity. In Haidt’s study of 23,000 self-identified liberals and conservatives, fairness, while not unimportant to conservatives, was identified as much more important to liberals. Other studies show that conservatives are more averse to change, and desire order and tradition. Attempting to always be fair can be inconsistent with maintaining order. Decades of research on conservative people suggests that their social views can help satisfy “psychological needs” to make sense of the world and manage uncertainty and fear. “People embrace political conservatism (at least in part) because it serves to reduce fear, anxiety, and uncertainty; to avoid change, disruption, and ambiguity; and to explain, order, and justify inequality among groups and individuals,” the researchers of a 2003 survey said.

The third moral foundation is in-group/loyalty. “Birds of a feather flock together,” as the saying goes. Haidt says that this moral underpinning probably comes from our long history of tribal living, and tribal psychology. Loyalty was found to be much more important to conservatives than liberals. It may also be linked to conservatives being wired to be more fearful of unknown groups (e.g. “they may do me harm”). Liberals are more curious and open to exploring diversity and forming new groups that may be comprised of different types of people, even though it might essentially be a new “in-group.”

The fourth foundation is authority/respect, and there is also a substantial contrast between liberals and conservatives here. Conservatives view it as important to follow traditional rules and respect authority—because, after all, it maintains order. Liberals seeking fairness and justice, on the other hand, believe that we should challenge rules that are unfair. It is not that liberals do not want rules, but rather that they desire equitable ones.

The fifth foundation is purity/sanctity. Haidt contends that, while the political right may moralize sex much more, the political left is doing the same with food. Food is becoming extremely moralized with ideas about purity, and about what people are willing to touch, or put into their bodies.

Haidt and his colleague concluded from this experiment that liberals’ moral compass is largely comprised of two morals: harm/care and fairness/reciprocity. Meanwhile, conservatives have a 5-fold set of morals that guide their political views, and for them, authority, in-groups, and purity are paramount. He is careful not to judge one moral compass as better than the other, or suggest that the research indicates that liberals are less moral than conservatives or vice versa. Rather, it is simply a matter of priority, focus, and, as other researchers have found, differences in brain functioning.

Jonathan Haidt’s Analysis of The Liberal Versus Conservative Moral Mind

So where do we being to find common ground? Why not start with the two values where there is not such a sharp contrast: harm/care and fairness/reciprocity.

| Moral Mind Characteristic | Liberals | Conservatives | Potential for Common Ground |

| Harm/Care | The current rules and traditions do not work for everyone and need to be changed in order to keep us all safe from harm. | Order, authority, rules, tradition, and status quo keep us safe, and I am less fearful when there are more of these things. |

|

| Fairness | It is the duty of the government to alleviate social ills and to protect civil liberties and individual and human rights. The role of the government should be to guarantee that no one is in need. Policies generally emphasize the need for the government to solve problems. | Value personal responsibility, limited government, free markets, and individual liberty. Government should provide people the freedom necessary to pursue their own goals. Policies generally emphasize empowerment of the individual to solve problems. |

|

If we start with self-understanding and what makes us believe in what we do (e.g. how our brains are wired) we can then move toward trying to reach common ground. In working to find common ground, it is important to be able see what the values look like behaviorally. What is happening when we respect the individual? What is going on when we promote individual responsibility and government intervention? It may take a while, but without identifying and addressing areas where we can agree, we will continue to be polarized and no progress will be made.

Hi Mary,

Thank you for this article, it’s been enlightening. I live in the Middle East and am trying to work out, among many other things, why Americans, liberal or conservative, would so quickly dismiss lives they can’t see. This covers the BLM movement but also why, Middle Eastern lives, which are put at risk daily by those American black, white, latino, asian lives – are all ignored in some capacity because of American lives, seemingly, mattering more, whatever your political background. I wish I could get my hands on more research like this. But thanks, this has been such a good read.