Have you ever made a mistake?

That’s not really a question, but this is: What do you do when you realize you made a mistake? Well, perhaps you apologize and try not to repeat it. Pretty simple, right?

Except what if others refuse to accept your sincere regret? When is saying sorry not saying enough?

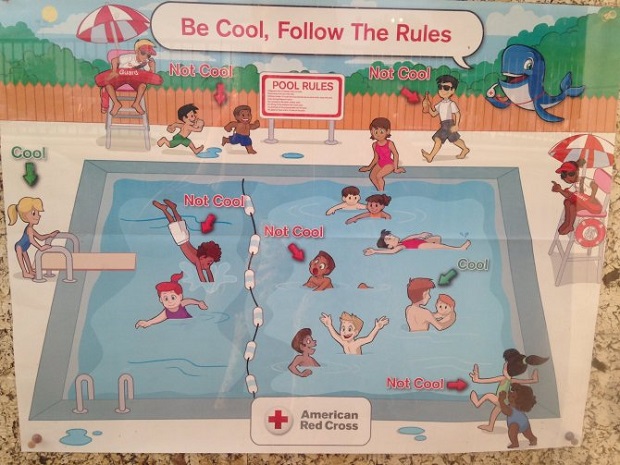

It’s a question I’ve been thinking about in light of the recent scandal surrounding an American Red Cross pool-safety poster. “Be Cool, Follow The Rules,” the sign implored, depicting a diverse array of children playing at a pool. After a woman had seen the poster at a Salida, Colorado, pool, she complained to her local NBC affiliate KUSA that the image was racist. The poster, originally created in 2014, cited white kids acting “cool” and black children behaving in “not cool” ways (running near the pool, pushing another child into water, etc.).

“It looks like they’re trying to do something there that shows all kids together of all different backgrounds, but they’re clearly not hitting the mark,” she said.

As a result, the Red Cross issued a statement: “We deeply apologize for any misunderstanding, as it was absolutely not our intent to offend anyone. As one of the nation’s oldest and largest humanitarian organizations, we are committed to diversity and inclusion in all that we do, every day.”

The company went on to say that it removed the poster from its site and app and notified all partners to take down the sign, adding that it’s “currently in the process of completing a formal agreement with a diversity advocacy organization for their guidance moving forward.”

That seems more than sufficient to me. Not so for Ebony Rosemond, the head of Black Kids Swim, a group geared toward helping black children learn to swim. Rosemond rightly points out that black boys and girls have faced a history of discrimination at public pools and insists that “images like the one created and circulated by the Red Cross make things worse.” An apology, she says, is insufficient.

But why? It would be one thing if the poster were part of a pattern of poor diversity-related decisions, but that doesn’t appear to be the case. The Red Cross appears about as committed to diversity as plenty of other well-meaning companies. Unfortunately, it seems like many people refuse to accept the notion that businesses, like themselves, are flawed. Companies make mistakes, too.

And so when a mistake appears to be just that, we ought to give businesses the benefit of the doubt. Is more diversity training necessary? Maybe. But maybe not. It depends on whether Red Cross’ blunder represents a broader problem. Even if the organization’s intent was good, given that the impact was anything but, this could typify an instance of unconscious bias—in which case there’s some room for education.

Frankly, whether this case shows unconscious bias or simply demonstrates a singular lapse of judgment, this is a teachable moment nonetheless. In reality, instances of unconscious bias happen all the time. Perhaps this event is a canary in a coalmine, but at the very least, it’s an opportunity for the company to reinforce its commitment to diversity and inclusion.

So was the poster racist? Yes. Does that mean that the company must do significant soul-searching, retrain its people, and issue more apologies? I’m leaning toward no. But should the Red Cross take this chance to highlight the potential impact of unconscious biases, even if they may not apply directly here? Absolutely.