Everyone, calm down. Cliff Huxtable never raped anyone. You can still enjoy reruns of The Cosby Show while dipping into your container of Jell-O pudding.

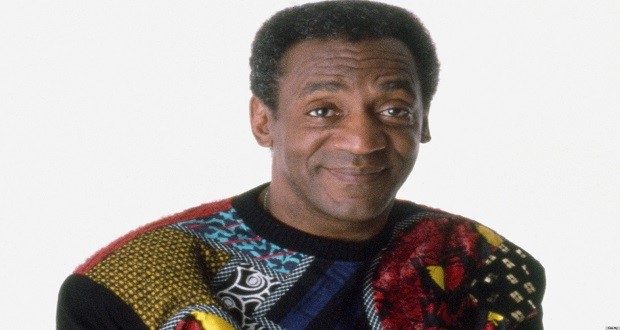

Bill Cosby, on the other hand, may be a bad, bad, bad person. The recent rape allegations against the iconic comedian are troubling, but not just for obvious reasons. They are particularly problematic because they’re targeted at someone who, as a recent New Republic article puts it, “made White America feel good about race.” And so, nobody wants to believe that the claims are true. Not White people. Not Black people.

But if both races shudder to think that a beloved father figure violated numerous women, then why did I even mention race?

Because to say that this case has nothing to do with race is like arguing that the O.J. Simpson fiasco had nothing to do with race. The two cases aren’t exact parallels, but when there’s vilification of a Black icon, whether race should matter is irrelevant. It matters.

And so it does with Cosby. The New Republic article points out that many of the new charges against Cosby aren’t really new. Around for many years, they never gained much traction in the media because as Gawker’s Tom Scocca puts it, “nobody wanted to live in a world where Bill Cosby was a sexual predator.” In other words, no one wanted to get serious about the star of one of TV’s greatest comedies.

But in The New Republic, Rebecca Traister writes:

“One reason that we have collectively plugged our ears against a decade of dismal revelations about Bill Cosby is that he made lots of Americans feel good about two things we rarely have reason to feel good about: race and gender. To confront the ugliness of Cosby’s alleged criminal misdeeds, especially in light of his rhetoric around racial responsibility, would mean reckoning with what was always fraught, false, or incomplete about his messages. It’s a process that is likely to make a lot of people feel very bad—not just about Cosby, but about ourselves and our nation’s persistent inequalities.”

Cosby showed White audiences that Black people could—surprise!—have families just as loving and normal (and rich) as their own. And Black audiences saw that—surprise!—White audiences could embrace such a portrayal.

Which is why any chips in his image can feel like betrayal to both races.

But we should all learn to separate the man from his messages about race, of which he was never in short supply after his show went off the air. That he may be a rapist should not discredit his opinions on race, the Black community, or his comedic genius.

Editorial Note: Vadim says that we should separate the message from the messenger. Can we? Should we? We would like to hear your opinion.