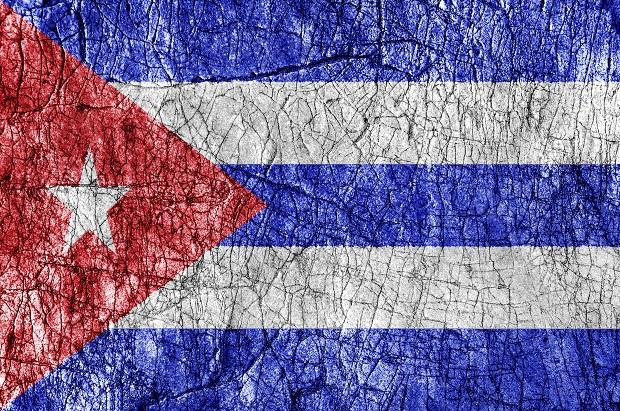

I just returned from a weeklong trip to Cuba that was unforgettable. Not only because Cuba is an interesting and beautiful country, but I was there during the historic death of Fidel Castro. This trip was bookended by my trip last year during Obama’s historic speech on improving US-Cuban relations. I will never forget being in a Cuban family’s house during Obama’s speech and seeing people jump and cry and dance at the hope of progress between Cuba and the US. This trip, during Castro’s death was so much different.

I had several friends ask me eagerly about what it was like being there during this time, I think in part they were curious whether there was anything similar to the celebrations of many Cubans in Miami on US television, or about what I was hearing on the ground from my Cuban friends. The answer is, it was eerily quiet. Granted, I was traveling in smaller cities this trip so I was removed from the big city life of Havana, but I didn’t see any public displays of celebration or contrition.

The whole country was in a mandatory 9-day period of mourning, which meant no alcohol, no live music, no theaters, optional hours of service for businesses and 24-hour documentaries on the life of Fidel Castro. And since the Cubans that I know do not feel safe to talk about their perceptions and feelings about the Cuban government and Castro—and I don’t feel comfortable bringing it up—I didn’t learn a whole lot while I was there. My friends have made it very clear to me, this trip and in the past, not to talk openly about the government—unless of course it’s in a positive light. So amidst all of the complexities that Castro’s death raised—US-Cuban history, capitalism versus socialism, fascism, etc.—I did what I normally do when I have more questions than answers, I went on Twitter to read reactions from other professors, political theorists, and other Cubans in the diaspora for more understanding. This is a journey I’m still on, as I think there is so much fruitful ground for mutual understanding between the US and our neighbor, Cuba.

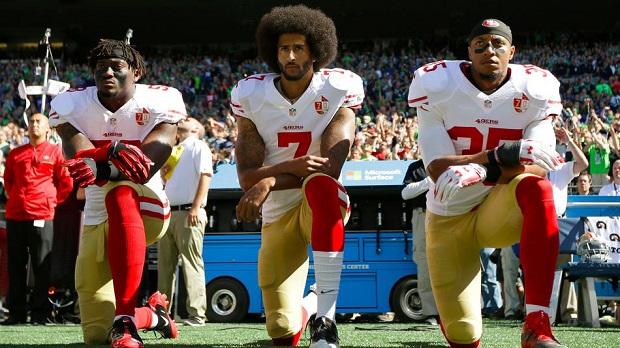

But from my friend’s silence, I did learn one important lesson: the value of our freedom of speech. Of course, our freedoms come at cost and have their limits, but I take it for granted that I can protest, critique, vote, and debate openly about our government and our politicians. This lesson is especially important now given the polarized times and nature of Trump and his exclusionary policies.

Like many of you, I have had many challenging and difficult conversations recently around issues of race, social class, police brutality and political policies of exclusion. And many of them have been critical in nature of Donald Trump and many of his supporters. But never once did I feel afraid to speak out and express my disgust and critical perspective—it is a privilege that I have, that I often take for granted. I know it may seem disingenuous to be thankful for conversations that may be triggering, tiresome, conflictual, and depressing, but I have a newfound sense of appreciation for the freedom to be critical and be in critical dialogue with others—especially compared to my Cuban friends who must use coded language in texts and practice strategies to steer political conversations in public towards another topic for fear of their safety. It is a freedom that I will cherish a little more tightly now; and maybe, one I’ll remember the next time I’m drained from a critical conversation or get discouraged about the possibilities for change through dialogue. The very ability to have them is a gift.