Being South Asian American in a predominantly white neighborhood, having melanin-heavy skin, and growing waist-length thick hair for many years growing up, people were always curious (luckily, usually with good intent) about my identity. When you stand out as being visually “different” in a space, “Where are you from?” “Can I touch your hair?” or (the most interesting,) “I wish I could be as tan as you,” are common questions and comments that friends, acquaintances, and even the person in line next to me at a coffee shop would say.

Now, disclaimer: I am all for giving genuine compliments; heck, I am more than happy you love my chocolate glow! That being said, there is a fine line between being intentionally curious and celebrating someone’s unique characteristics, and exoticizing or taking ownership of these characteristics as “authentic” and “cultured” without understanding the implications of appropriation and disempowerment of less-dominant identities. Like many conversations we have unpacked in this series, these comments have come from a long history of American culture “exoticizing” certain aspects of people of color. Exoticizing can be thought of as portraying something different as unusual or glamorous, while leaving the culture itself in the dust.

There is a fine line between being intentionally curious and celebrating someone’s unique characteristics, and exoticizing these characteristics. Share on XSo why are we still having this conversation? Calling out cultural appropriation in America is not a novel idea (think: Halloween costumes, Native American headdress, etc.), yet appropriation has been institutionalized across many industries. The increased globalization and diversification of our country has led to the desire for the most “authentic” experiences. But, how can we find authenticity if in fact what is deemed authentic is defined, coined, and ultimately profited upon, by members of the dominant identity? These underlying dynamics ultimately disempower those of non-Eurocentric cultures, and ultimately, perpetuate the idea that Eurocentricism, or whiteness, is normal or best.

Can I touch your hair?

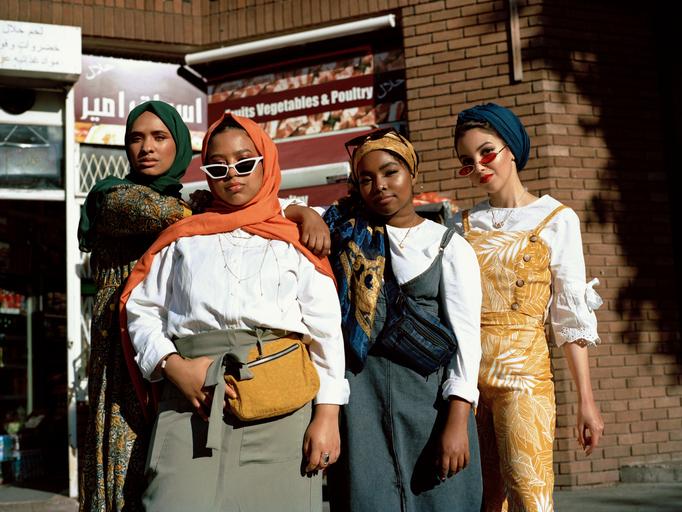

Sure, you may want to touch someone’s hair because it looks like it is different from yours, and I am certain it is because you admire and appreciate it. However, this comment goes way beyond admiring locks; objectifying and exotifying women of color, African-Americans in particular, has been a long part of slave history in America and Europe. Black women have literally been put on display over the course of history—think zoo-like shows and exhibits—all while being dehumanized and abused physically and emotionally. This history continues to live on in the way Black people are treated today, through such instances as being asked to touch their hair, and most recently, “Blackfishing” — white people pretending to be black online by appropriating specific, desired parts of black beauty and appearance for social media fame and influence.

Besides just the blatant disrespect of bodily space, think about it in terms of the societal implications: imagine if someone asked to touch your hair or that you were complimented at a restaurant, while in other settings you are likely to be discriminated against at a job interview or criminally profiled because your hair is deemed “unpolished” or “unprofessional.” Instead of touching, try supporting systemic change for true appreciation and respect for Black communities. Standing in solidarity can amplify change: just this week, Montgomery County Maryland and Cincinnati announced plans to ban discrimination against natural hair.

Where are you from? …But where are you REALLY from?

“Where are you from?” is really an innocent question most of the time — I even see it as a way to find shared meaning with people who may share similar identities as me, such as ancestry in the same part of India, being born in the same part of Kansas, etc. Yet, many times, strangers and acquaintances ask this to understand my racial/ethnic identity (Indian) and proceed to defy the authenticity of my response. Sometimes this sounds like, “Oh, I’ve been to the Taj Mahal, India is amazing!” …followed by their shock and disappointment when I say I have never visited the same place. Or, most memorable: “You look more South American,” or, “But I thought you were Armenian because of your last name!”

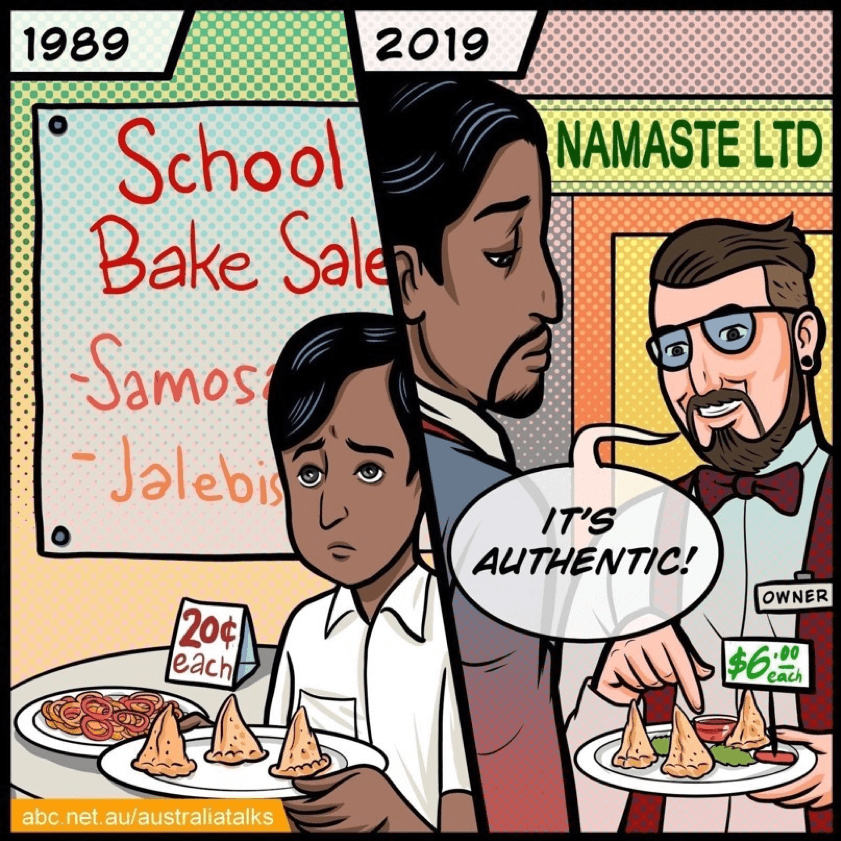

The problem isn’t the question itself, but rather, the intent behind it and the follow-up. What is it that you are trying to achieve? Are you confused that this person didn’t automatically give their ancestral background, or that their answer doesn’t fit the idea of where you think they should be from? The systemic implications of this question are evident in an often-hidden reality: the ways that attitudes on “ethnic” foods have changed over time. Decades ago, when Asian or Mexican immigrant children brought their meals for lunch, they were ridiculed for being “gross” or “smelly.” However, nowadays, some food entrepreneurs have capitalized on “ethnic” food offerings as the newest food trends, often cultivated to fit the expectations of what is considered “authentic” according to Eurocentric and western ideals. This comic from ABC Net Australia sums it up well:

So, next time you hesitate to ask someone where they are from, think about how you can redefine what it means to connect with others authentically. Empower them to be proud of where they are from, instead of having to justify their entire identity. Maybe ask your friend to learn more about the history of yoga, acknowledge the privileges of being able to travel and what your plans are: Are you intentionally not seeing what you don’t want to see? Or, ask to try a family recipe for a Spanish meal, instead of going to the trendiest new tapas bar. These are intentional ways of appreciating someone’s culture without using curiosity as a means to scrutinize their lived experience.

I wish I could be as tan as you.

Every time I hear this, (or its adjacent, “I wish I was more ethnic,” and similar comments) whether they are directed to me or someone else, I can only think of the irony. Colorism, favoring those with lighter skin and discriminating against people with darker skin, continues to prevail as the standard of beauty—and ultimately power and privilege—in many cultures from Asia, South America, and Africa. When I hear this statement, I hear the unspoken afterthought: “I wish I could be as tan/ethnic as you, BUT, I don’t want to be a person of color.” You don’t wish you could be discriminated against or have less power in society. Ultimately, people’s lives are lost because of the color of their skin. And, while the intent is rarely malicious, appreciation of the amount of melanin someone has is blatantly ignoring the meaning behind our melanin that was constructed by white people, and ultimately internalized among communities of color.. Instead of objectifying and sensationalizing the diverse appearances of those with non-dominant identities, we can celebrate with our friends of different ethnicities. Ask yourself: why do I want to be more “tan?” Who is telling me to be this way, and what does it cost me or my peers? If you desire authentic intercultural experiences, you might want to consider: how can I intentionally, and with empowerment from my diverse friends, show my appreciation for the culture instead of yearning for a superficial aspect of it?

No matter how you identify, recognize that appropriation is NOT appreciation. Share on XUltimately, no matter how you identify, recognize that appropriation is NOT appreciation. To have meaningful and intentional relationships in our increasingly diverse world, I encourage us all to think about how we can use our different levels of power and privilege to redefine authenticity, and empower, not exoticize, our differences.

To have meaningful and intentional relationships in our increasingly diverse world, I encourage us all to think about how we can use our different levels of power and privilege. Share on X