The following was taken from a chapter that I contributed (From Diversity to Inclusion: An Inclusion Equation) in the recently released book, “Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion” edited by Bernardo Ferdman and Barbara Deane (Jossey-Bass, 2013).

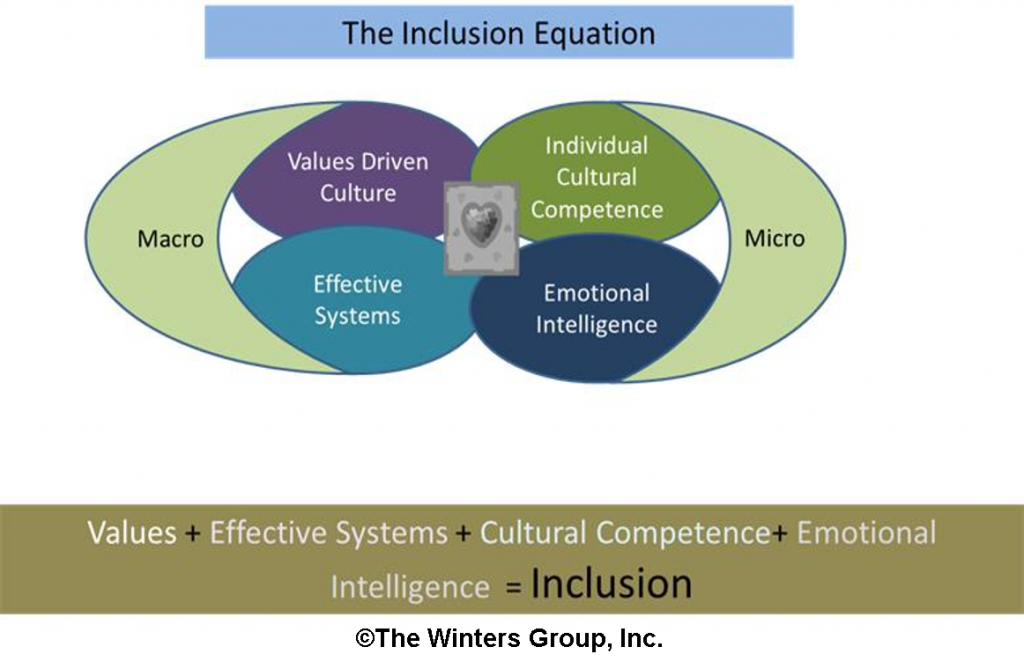

Inclusion is simultaneously about the macro and the micro. It is most effectively driven both via top-down leadership and bottom-up engagement. It is about systems and values, as well as the individual. Inclusion will only be sustained when all three are addressed:

- Systems: Policies, procedures, programs, and practices provide the foundation for creating an inclusive culture. However, the right systems by themselves are not enough. The interdependence of the systems must be recognized, and the systems must be managed and delivered by culturally competent leaders who truly believe in the tenants of inclusion.

- Values: Inclusion must be explicitly connected with the vision and values of the organization, a part of the DNA, if you will.

- Individuals: People experience inclusion or exclusion based on day-to-day interactions with supervisors and peers. The organization’s policies and vision can be perfectly stated and well-intended, but the real test of inclusion is the extent to which employees feel welcomed, valued, respected, and acknowledged for their contributions. My assertion is that leaders who are culturally competent and display higher levels of emotional intelligence are more likely to create an inclusive environment.

I have created the inclusion equation to help depict the interrelated variables necessary to create and sustain inclusive cultures.

In this post I will focus on the macro part of the equation.

Inclusion is a value, and as such must be inherent in and integrated into all aspects of an organization’s culture. Values are the moral compasses that guide organizational behavior. Like other values employees are expected to “live,” inclusion must be comprised of a set of behaviors that are meaningful across a variety of backgrounds and cultures.

Living one’s values happens one action at a time, and often the little things, such as saying “good morning,” send a message of inclusion–or exclusion. Just like most values, inclusion is conceptually simple, but complex to consistently implement. From my work with different types of organizations, it is clear to me that leaders who are already values-centered will more easily embrace inclusion, and more effectively execute inclusive policies.

At a systems level, Human Resource policies such as recruiting, onboarding, succession planning, high potential identification, leadership development, work-life balance, accommodations for differently abled employees, benefits, rewards and recognition, and performance systems all need to support the goal of inclusion, and many organizations’ written policies do so today.

However, many large companies have launched robust diversity and inclusion initiatives, only to find their struggles continuing as a result of inconsistent implementation. Strong implementation depends on the quality of leadership responsible for interpreting and executing the policies and the extent to which those leaders are held accountable. As an example from the HR policy perspective, a diversity strategy for recruiting may be in place, but individual recruiters sometimes systemically screen out diverse candidates based on their own unconscious bias. As another example, organizations can claim to offer flexibility to support work-life balance. However, in conducting focus groups over the last five years for several clients, a consistent trend emerged. Respondents agreed the policies were in place, but they also agreed it would damage their careers to take advantage of them. Managers often subtly discouraged employees from taking time off or working from home.

Next week, I will discuss the micro aspects of creating an inclusive culture.