Trump began his presidential campaign by notably stating, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

At a New Hampshire rally in 2015, Trump pledged to kick all Syrian refugees, mostly Muslims, out of the country, implying they might be a secret army. “They could be ISIS, I don’t know. This could be one of the great tactical ploys of all time. A 200,000-man army, maybe,” he said. In an interview that aired later, Trump said: “This could make the Trojan horse look like peanuts.”

Still during his campaign, Trump raised doubts about U.S. District Judge Gonzalo Curiel, who was presiding over a civil suit of fraud charges regarding Trump University. In a June 2016 interview, Trump said that Curiel had “an absolute conflict” in deciding the case because he was “of Mexican heritage.” Following other statements he has made about combatting illegal immigration, Trump stated, “I’m building a wall. It’s an inherent conflict of interest.”

Last January, Trump’s ‘shithole countries’ remark when referring to El Salvador, Haiti, and Africa, spurred international anger. International organizations, including the UN and the African Union, politicians, and individuals from Africa and the Caribbean expressed outrage over such racist remarks. Morocco-based African analyst Adama Gaye told Al Jazeera: “Trump has shown a continuous display of racism towards Africa.” Abdulsalam Kayode, a resident of Lagos, Nigeria’s capital, told Al Jazeera: “These are racist comments. He has said things like this before when he talked about Nigerians who won’t go back to live in huts and he talked about Haitians who bring AIDS to the United States. These are all confirmations of what a lot of people have long suspected – that he harbours racism.”

In October 2018, the president insisted that a caravan of several thousand Hondurans was coming to the United States. For several weeks, the president insisted on making the caravan into a national emergency. In fact, he sent troops to safeguard the border. Trump falsely told his supporters that there were “criminals and unknown Middle Easterners” in the caravan, a claim that had no basis in fact and that was meant to imply that terrorists were hiding in the caravan. In reality, the caravan was thousands of miles and weeks away from the U.S. border, shrinking in size, and unlikely to reach the U.S. before the midterm elections. There was no national emergency or ominous threat–only a group of desperate people looking for a better life, who, by the way, do have the right to request asylum in the United States; they also have no right to stay if their claims are rejected. Trump was reportedly aware that his statements about the caravan were not true. An administration official told The Daily Beast, “It doesn’t matter if it’s 100 percent accurate … This is the play.” This so-called “play” was used to demonize vulnerable people and to frighten Trump’s base into the polls.

In Nov. 2018, Trump went after Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.), launching a Twitter attack against the outspoken congresswoman just a week after she and other Trump critics were targeted in attempted mail bombings. Waters, a fierce critic of the president, has been the subject of a number of attacks from Trump, both on Twitter and in rallies. He frequently derides her as “crazy” and an “extraordinarily low IQ person.”

Looking back at

Trump’s comments, one can easily see what they have in common: they are racist,

they denigrate others, they position the U.S. culture above others, they are

polarizing, they are insensitive, and they elicit an “us versus them”

mentality. Fear of foreigners and dehumanization permeate the rhetoric of this

administration. Keep on reading to understand

why.

What

individuals need in order to work effectively across differences

In Preparing advisors to work effectively across differences: A three-step framework (NACADA, 2010), I discussed a couple of frameworks that were developed to help individuals become aware of, understand, and develop the skills to value diversity. One of the frameworks discussed was the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS), created by Dr. Milton Bennett (1986, 1993, 2004, and 2013). Using concepts from constructivist psychology and communication theory, Bennett explained how individuals evolve in the way they deal with differences by positioning them along a continuum of increasing sensitivity to differences.

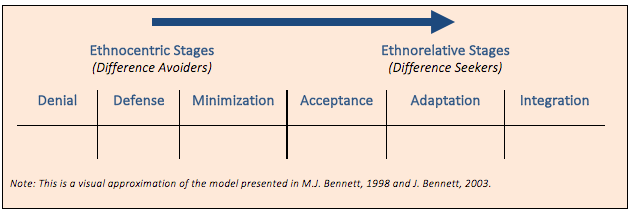

According to the DMIS framework (see figure below), there are six developmental stages we go through in our journey to deal more effectively with differences—be it differences related to nationality, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, religion, and all other differences learned or shared by a group of individuals.

Individuals in the first three stages tend to be difference-avoiders and have an ethnocentric perspective. In other words, they use their own cultural lenses to view other value orientations. Those in the last three stages are difference-seekers. Their ethnorelative perspective allows them to see their own culture in the context of other cultures (Bennett, 2003). In order to function effectively in an increasingly multicultural and global society, we all need to understand where we are on the continuum and take the necessary steps to move on to the next stage.

A brief explanation of the different stages

Denial of cultural differences. In this stage, individuals are unaware that certain types of differences exist. They either don’t recognize cultural differences or, at best, only see broad, stereotypical categories. In their minds, only their culture, values, and norms are legitimate and they use this sole framework to analyze all other cultural orientations.

Defense against cultural differences. Those defensive about cultural issues do recognize differences; however, they negatively label the norms, values, and behaviors that differ from their own. They demonstrate an us-versus-them mentality in which they see their culture as superior to others. Cultural differences tend to be very challenging for individuals in this stage.

Minimization of cultural differences. Individuals who minimize differences hold the general belief that, deep down, we are all the same. As a result, they may think that they “do not have to do the difficult work of recognizing [their] own cultural patterns, understanding others, and eventually making the necessary adaptations” (J. M. Bennett, 2009). They expect that culturally diverse individuals will adapt their ways to those of the dominant culture. Color-blindness is a typical mind frame of individuals in the minimization stage.

Acceptance of differences. This is the gateway to inclusiveness, so to speak. Acceptance of differences shifts individuals from difference avoiders to difference seekers. Individuals at this stage recognize differences in values, norms, and beliefs and are interested in learning more about the diverse populations they serve so they can work more effectively with them. Cultural differences are relatively less threatening to them, and they are able to suspend their judgment (at least temporarily) so they can understand the perspective of others.

Adaptation to cultural differences. When ready to adapt to differences, individuals are able to change their behavior to interact effectively across differences. They know enough about their own culture as well as the culture of others to successfully “code-shift” (J. M. Bennett, 2009) into the value scheme of others. They have the ability to operate in more than one cultural frame of reference and have highly developed inclusiveness and collaboration skills.

Integration of cultural differences. Reaching this stage can only be accomplished when individuals intentionally make a significant and sustained effort to become fully competent across differences. Those in this stage are truly bicultural or multicultural; they not only thrive on cultural differences but they are also very good at bridging differences. They can look at situations from multiple frames of reference and shift easily from one cultural frame to the other. Most individuals do not reach this stage. In any organization, expect that individuals will be at different stages on the DMIS continuum. Moving from one stage to the other will require a lifelong, gradual process of learning to be aware of and understanding cultural differences as well as acquiring the necessary skills to work effectively across those differences. At the very minimum, we all need to be operating at the “acceptance” stage because that is when we start understanding and valuing diversity.

How Trump ”deals with” diversity

Looking back at Trump’s comments and actions, not only throughout his presidential campaign but also throughout his presidency so far, I would place him somewhere between the “denial” and “defense” stages. Below, I will explain why.

“Denial” is the purest form of ethnocentrism. Individuals at “denial” are not able to see differences, or when they do, they only see broad, stereotypical categories. For example, when they think about Africa, the only images that likely come to mind are wild animals, jungle, black people, and poverty. Think back to Trump’s comment about Nigerians not wanting to go back to live in huts—as if huts were the only type of housing available to them. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns us against the dangers of having a single story (i.e., thinking of Nigerians as only living in huts) in her 2009 TedTalk. She argued that “single stories create stereotypes and stereotypes are incomplete because they become the only story.” Constantly thinking of other cultures in stereotypical ways reduces them to a simplistic model and it robs them of all the other possibilities that could be.

Isolation and separation are typical mind frames of those at the “denial” stage. In fact, the intentional erection of physical or social barriers from those who are different is not uncommon. Remember the border wall? Mexico and the United States share a border over 1,800 miles long. However, their standards of living are not the same: the United States is one of the richest countries in the world whereas 42% of the population of Mexico is poor. In 2016, it was estimated that 12 million immigrants from Mexico are living in the United States; about 45% of those are undocumented. These immigrants cross the border, often risking their lives, in the hope of a better life. Donald Trump was elected with the promise to make the United States great again. He believes a strong country is a country with closed, well-guarded borders, and he promised to protect the United States by building a 1,000 mile-long wall along the border.

Isolation and separation are typical mind frames of those at the “denial” stage. In fact, the intentional erection of physical or social barriers from those who are different is not uncommon. Remember the border wall? Click To TweetI also see Trump demonstrating strong characteristics of those who are still in the “defense” stage. These individuals do see cultural differences; however, they attach a negative evaluation to them. There is a posture that differences are threatening. In fact, individuals in this stage are very stressed out about differences.

I also see Trump demonstrating strong characteristics of those who are still in the “defense” stage. These individuals do see cultural differences; however, they attach a negative evaluation to them. There is a posture that… Click To TweetDenigration and overt negative stereotyping are also common of those in the “defense” stage. The most common strategy to counter the threat of difference is to negatively evaluate it—often with undesirable characteristics being attributed to every member of a distinct group. Trump’s comments about Mexicans being rapists, bringing drugs, and bringing crime to this country attest to that. His “shithole countries” remark is another example. Trump also has a long history of anti-Muslim remarks, including saying in 2015 that he would “strongly consider” closing mosques in the United States, declining to rule out the creation of a national Muslim registry, and saying during a 2016 CNN interview, “I think Islam hates us.” He seized on the issue again in the wake of the massacre at a gay nightclub in Orlando, reiterating his support for blocking Muslims from entering the country. He also alleged that many American Muslims and mosques are knowingly protecting terrorists, that the United States should consider profiling Muslims, and that Obama was in league with Islamist extremists.

Those in the “defense”

stage think nothing about denigrating others. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) and

Serge Frank Kovaleski, a South African-born

Australian-American investigative reporter at The New York Times, were on the

receiving end of Trump’s denigration. In a profile for Rolling Stone, Trump

was quoted as saying about his primary rival Carly Fiorina, “Look at that face! Would

anyone vote for that? Can you imagine that, the face of our next

president?!…I mean, she’s a woman, and I’m not s’posedta say bad things, but

really, folks, come on. Are we serious?”

Behaviors

of an inclusive leader

In the vast literature on inclusive leadership, we can easily find a list of important traits and competencies of inclusive leaders. In fact, researchers argue that inclusive leaders:

- Are self-aware

- Advocate for and appreciate diversity

- See situations from others’ perspectives

- Accept different beliefs and behaviors

- Adapt their behavior to work with other individuals and cultures

- Champion differences

- Talk about differences without making anyone feel objectified or singled-out

- Work to understand their biases when making assumptions about others

- Are aware of their own stereotypes and prejudices

- Know how to use power with responsibility

- Understand the interdependency between people

- Have a desire to learn about others

- Make inclusion a priority

In Inclusive Leadership: A Theoretical Framework, the authors go as far as arguing that becoming an inclusive leader requires that you fully accept others with all their strengths and weaknesses. In addition, you have to be willing to learn and challenge yourself to go the extra mile to become an inclusive leader. This is an ongoing journey that requires small steps and time to be achieved. Given his demonstrated inability to show appreciation for diversity, to talk about differences without making others feel objectified or denigrated, coupled with the disturbing reality that Trump’s modus operandi is one of demeaning others, inciting fear of foreigners, overt racism, and dehumanization, the potential for our achieving inclusiveness and seeing less polarization in this presidency is not very promising.

Lastly, I want to reiterate that my writing this article has nothing to do with political partisanship. Instead, it was an attempt to use a widely known, highly researched theoretical framework (DMIS), which, in fact, is used worldwide to help create culturally competent services and organizations, to try to understand the polarizing tendencies of this president. Unfortunately, what it showed is that this president still has a long journey ahead of himself as far as working effectively across differences. More worrisome is that we have someone in a global leadership position who lacks a global mindset as well as the skills to lead inclusively.

This president still has a long journey ahead of himself as far as working effectively across differences. More worrisome is that we have someone in a global leadership position who lacks a global mindset as well as the skills to… Click To Tweet