By my junior year in high school, I knew I wanted to attend a women’s college. As my college search wore on, the co-ed schools I had considered gradually dropped off the list until, inspired by older friends who had taken the women’s college path before me (and my 17-year-old stubbornness), I submitted my deposit to my number one choice: Wellesley College. To anyone who dared question this choice or offer the unsolicited “I could never be only around women—too much drama,” I retorted with an empty phrase I had memorized: “That’s sexist. Women’s colleges are empowering!” And empowered I would become—not without with some bumps along the way.

At the same time I was preaching the gospel of feminism around my high school and craving the surroundings of the empowered women that I encountered on my college visits, some of my attitudes betrayed contradictions that complicated the picture of me as an enlightened feminist. I regularly discussed with a friend how, when I had children, I wanted boys. On one of my college tours, I saw a museum advertising an exhibit about the history of women in dentistry and thought, “How boring.” Increasingly, I opted for androgynous or masculine clothing and presentation over feminine—more out of principle (“gender is a social construction!”) than what felt right to my personal identity. Somehow, I saw no irony in any of this.

At the same time I was preaching the gospel of feminism and craving the surroundings of empowered women, some of my attitudes betrayed contradictions that complicated the picture of me as an enlightened feminist. Share on XI went on to attend my first year of college and declare a Gender Studies major. I loved my classes but pointedly enrolled in those that explored gender or sexuality broadly rather than so-called “women’s issues.” My heroes at the time were homogenous—a list of quirky white men. I had developed an essentialist talking point that would make my high-school-self and current-self alike cringe for anyone who asked me how I was liking college: “It’s going well, but sometimes I miss men. I feel like they bring a sense of levity to spaces that I miss.”

Perhaps most ironically, it wasn’t until I enrolled in a summer class—not at Wellesley but at my local community college—that I recognized my problem for what it was—internalized sexism.

Ironically, it wasn’t until I enrolled in a summer class—not at Wellesley but at my local community college—that I recognized my problem for what it was—internalized sexism. Share on XIn pursuit of minimizing my course load senior spring, I reluctantly registered for a women’s literature course offered in the summer at my local community college. True to character, I wasn’t interested in reading about Virginia Woolf’s concerns, and anyway, I hated analyzing literature (or so I thought, based on my experiences in high school.) Yet, it was the only summer class that could count towards my Gender Studies degree back at Wellesley, so enroll I did.

It would be an understatement to describe this class as anything short of a revelation. In the pages of the texts I was assigned, I encountered women writing cleverly and artfully about how women have been systematically underrepresented in history and the literary canon. “Hmm. That makes sense,” I thought, recalling the “classic” literary works I had been assigned in high school: Shakespeare, Joyce, Hemmingway, Conrad. I read accounts by women of how the world turns women against one another. I recalled those women who had insisted to me that a campus full of women could only spell drama and thought, “Wow. It’s true.” Other poets and authors wrote about experiencing a bodily self-consciousness in female forms that I found uncomfortably familiar—because, I realized, I recognized it in myself.

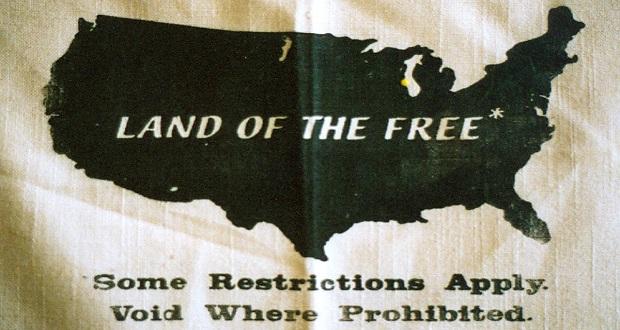

It was time to take a good, hard look at my innermost attitudes. I suddenly realized that I needed to reckon with the many ways I had swallowed the harmful message that I, like so many people, had been hammered with from as soon as I could consume media: women and girls are less interesting, less fun, less funny, more superficial, and higher maintenance than men and boys. (And, I now realized, it was no wonder I saw things this way, having encountered relatively few women-centered perspectives or heroines in my formative years.)

I realized that I needed to reckon with the ways I had swallowed the harmful message that I had been hammered with: women and girls are less interesting, less fun, less funny, more superficial, and higher maintenance than men and… Share on XOnce I recognized my internalized sexism, I could see my behaviors and attitudes in recent years aligning to confirm it in ways that seemed obvious in hindsight. While on some level I did respect and value women, I had ignorantly and hastily written off certain aspects of femininity as false or detrimental and worked to neutralize my own identity as a woman in any way I could. I would be a mother…of sons. I would be a woman…but a pragmatic, androgynous, gay, and unfussy one. I had been operating from a place where I felt women were, at best, “the same” as men, and thus deserved no special attention. This was a mighty act of cognitive dissonance to be certain, as I sought out an institution the very purpose of which was for women to receive special attention that they had historically been denied. I am grateful that the superficial understanding of feminism I embraced as a teenager at least managed to land me where it did.

Fortunately, once I returned to Wellesley, I had only to look around me to see beyond the sexist messages I now recognized I had absorbed. I was surrounded by brilliant, fun, and funny women, doing and being and creating amazing things. Being in this environment helped me to deeply reflect upon and come to genuinely value my identity as a woman—and subsequently, to embrace to some of the self-expression I had previously curtailed in effort to reject elements of my femininity. I made the most of my last year in this incredible space created for women, recognizing anew how fortunate I was to have this opportunity—one I would wish everyone could experience for an identity important to them.

Now, when I encounter women saying things like, “Women are so catty!” I grit my teeth and take a deep breath, remembering how and why, not long ago, I myself bought into messages that were not so different. Challenging years, even decades, of internalized messages like this to help people see beyond them is a Herculean task that will never be achieved in one conversation. Instead, I do my best to exercise patience, while challenging these notions with truths from my experience. “That’s interesting. People often hold that stereotype, but I spent four years surrounded by women, and they were some of the best of my life.”

These days, I make a concerted effort to ensure that the media I consume is at least somewhat balanced in the perspectives it highlights and work actively to recognize inspiring women and girls. If and when I have children, regardless of their gender identity, I will prioritize instilling in them a deep respect for women—by highlighting diverse heroines throughout history and in current events, by exposing them to media that centers and celebrates women, and by sharing examples of harmful messages they may encounter about women and girls in the world. I believe that actively and regularly taking steps to counter negative biases embraced by our culture and our media is our only hope of pre-empting or interrupting our internalizations of them. Consider—what are you doing to counter biases you and people you care about may be internalizing?

I believe that actively and regularly taking steps to counter negative biases embraced by our culture and our media is our only hope of pre-empting or interrupting our internalizations of them. Share on X

Editor’s note: The Winters Group created a reflection guide on this Inclusion Solution series. The purpose of this guide is to revisit the perspectives shared and to encourage greater self-reflection and critical thinking about the ways this topic influences your world. Also included in this guide are activities and reflection questions for you to engage in as you begin your journey. Download the guide here.