Source: Culture Trip

The simple act of play or leisure can be limited depending on if one is a low-, medium- or high-income earner. While this is an uncontrollable play of economics in our current systems, it is worth reflecting: what kind of policies or designs make it so that the simple and necessary parts of life — such as fun or relaxation — depend on how much income one has earned?

What kind of policies or designs make it so that the simple and necessary parts of life — such as fun or relaxation — depend on how much income one has earned? Share on XThe first thing to consider is how much city planners are providing spaces such as parks or streetscapes for social connections. An estimate of 689 million people globally live in extreme poverty of $1.90 or less a day[1]. Do these spaces for leisure require payments above average daily earnings to enjoy? Do public spaces truly function as communal points for everyone, or are there several segregated points that cater to just one spectrum of the economic scale? This line of questioning is not to challenge the concept of building around viable markets… but with economic declines in both developing and developed countries, should designs not consider more accommodating steps moving forward? To further emphasise the value of communal spaces, let’s reflect on some of the findings from related studies.

The lockdown was a period of social isolation and exclusion in cities. Yet, people still wanted to go out, see friends and families, or just spend time outdoors. So, this tells us that limiting access does not decrease demand for public spaces. In 2020, the Gehl team took to the streets to study this new type of public life in Copenhagen and New York. The team observed a 21 percent increase in people eating, socialising or partaking in other recreational activities around their local neighborhoods[2]. Although finding space can be difficult in more populated cities like New York, it was clear that while some areas witnessed a drastic reduction in public life, local neighborhood meeting places had simultaneously been thriving. Hence, it is valid to question what provisions are made for people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, and coping mechanisms in the absence of such.

For cities like Lagos, Nigeria, there is already an appropriation of public space that is often regarded as an informal extension of the city that needs to be curbed. However, these street spaces and open parks form intricate parts of both economic and social life[3]. So again, how can we move away with these ideologies?

Do low-income earners really care?

As much of a vital part as this is for cities, the pending question is, do low-income earners truly care about the subject of leisure? I once did a study in the heart of Lagos, Nigeria, called Eko-market, asking 62 residents and shop-owners how they spent their free time and how often they visited the popular spots around them. Note that Lagos Island is a mix of diverse historical and cultural sites that have been converted to parks, open spaces and restaurant spots. Yet, over half of those I interviewed were not familiar with the recreational spots in their communities. Likewise, business owners in the area highlighted the cost to access recreational spaces and the cost of travel as a challenge. The older residents in the area seemed to have more engaging stories… with what existed pre-independence. It seemed that with fewer restrictions from cost or distance that had played out along with development, earlier generations were able to truly experience their communities in a way that is no longer accessible.

Source: Culture Trip

In a similar approach, I spent a week observing how the security men in a community used street spaces for social activities. A tree close to my flat was usually surrounded by at least three wooden benches. In the same manner of old folk tales being told round a tree, community members would gather to play card games or listen to the radio in the evening on some days.

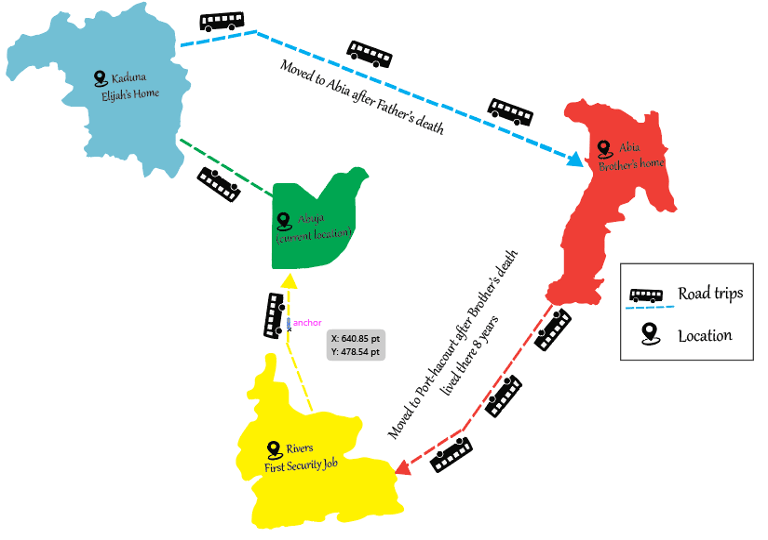

On my last day, I decided to ask my security man, Elijah, a few questions about his social life. The conversation went deeper into where he had spent his life. He talked about growing up in Kaduna but leaving after his father died. Elijah then moved to Abia State (Eastern Nigeria) to live with his younger brother at 10, and finally relocated to Port-Harcourt (Southern Nigeria) after the death of his brother. At that point, a friend connected him with his first security job in the city, where he spent the next eight years of his life.

At this point in the story, I paused to get a sense of the social life in the city where he spent most of his young adult life. He talked about a place called Polo Avenue in Port-Harcourt, which cost between 300-500 naira to access.

Source: GruvCity

After eight years, Elijah eventually moved to Abuja, which is the Federal Capital city of Nigeria, in 2020. His mother wanted him closer to home for the family in Kaduna (Northern Nigeria), especially with the uncertainty from the pandemic.

However, moving down to Abuja had not been a socially fulfilling experience for Elijah in the last year. He was particular about not knowing people around town or places to go to. He did share his experience going to parks by the lake closer to town, and the parking lot used for football by the fish market. While these two spaces are free to access, it was clear that it felt less feasible for him to explore the city with the demands that come with earning a living as a gateman, with the goal to save and eventually buy his own car as a taxi driver.

At this point, I chose not to probe any further into his expectations of a social life in our community. From his story, I knew he had been to more parts of the country than I would probably visit in my life; most of his movement was driven by the desire to earn a substantial living for himself and family. Maybe for him, the most important thing is having a place that can become anything at any time.

The purpose of observing and eventually interacting with our security guard was to get a sense of how people found ways to connect with spaces around our neighborhood. But at the end of our discussion, it seemed like income overruled the narrative for leisure for him.

Maybe, then, a critical need in design is leaving spaces like those we may have in front of our homes for people with little money and time to re-invent for themselves. That an open parking spot close to the fish market nearby is converted to a football field at night still hints to the importance of access to public space in our cities.

A critical need in design is leaving spaces for people w/little money to re-invent for themselves. That a parking lot is converted to a football field at night hints to the importance of access to public space in our cities. Share on XThe “right to the city” can no longer be just an idea or slogan[4]. Elijah is just one point in a wide web of stories, but it’s really a starting point for planners and policy makers to understand how simple, functional cities can be designed. So, as we continue to develop our cities post-Covid-19, how can we ensure people have spaces to relax, center themselves or just connect, regardless of income?

As we continue to develop our cities post-Covid-19, how can we ensure people have spaces to relax, center themselves or just connect, regardless of income? Share on X

Reference

[1] The World Bank Group. (2020, October 7). Poverty. The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview

[2] Schuff, Sophia. 2020. “How COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of public space in cities.” Government Innovation. https://cities-today.com/industry/covid-19-demonstrated-importance-public-space-cities/.

[3] Lawanson, T., Foley, L., Assah, F., Mogo, E., Mapa-Tassou, C., Ogunro, T., Onifade, V., & Oni, T. (2020). The urban environment and leisure physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a view from Lagos. Cities and Health. 10.1080/23748834.2020.1806459

[4] The Right to the City envisions cities and human settlements as common goods that should be shared and benefit all members of the community.

Nice and amazing