In Derrick Bell’s 1980 Harvard Law Review comment piece titled “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma,” he shared his analysis of the landmark court case wherein racial segregation in schools was ruled unconstitutional. While this seemed like a big win for the work toward racial justice, Bell described the shift from separate but equal to desegregation as a political ploy to improve the U.S. image concerning race relations. And, in so doing, he methodically exposed the ways in which racism metamorphoses based upon the needs of the hegemonic order. In this phenomenon — interest convergence — “The interest of [B]lacks in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of whites” (Bell, 1980, p. 523). The theory of interest convergence provides a lens for understanding Brown v. Board of Education and other major changes to the social order in which the power structure enacts policies that appear to be in the interest of subjugated or oppressed communities, yet is really intended to serve the best interest of those in power.

The theory of interest convergence shows the social order in which the power structure enacts policies that appear to be in the interest of oppressed communities, yet is really intended to serve the interest of those in power. Share on XWith this lens, we can think openly about the work toward justice and begin to interrogate whether intentions meet the goals toward liberation. In feminist poet Audre Lorde’s famed quote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” I’d like to suppose that she was speaking more to the essence of what has been built rather than the dwelling itself. So, when the tools used are steeped in capitalism and supremacy, one can expect adversity, subjugation, and oppression to be born from them. Despite the veneer of aligning interests, the benefits for those brokering power far outweigh those for the marginalized. As a type of capitalism, there are many forms of hegemonic interests attempting to usurp justice projects and moves toward liberation in our daily lives.

When the tools are steeped in capitalism and supremacy, we can expect adversity, subjugation, and oppression. Despite the veneer of aligning interests, the benefits for those brokering power far outweigh those for the marginalized. Share on XInterest convergence is evident in our public policies and laws. In addition to the aforementioned case, consider another matter of public concern: affirmative action. When affirmative action was written into law, the intended goal was to ensure that women and minoritized individuals had equal access to employment and education. While we have seen an increase in access in those areas for minoritized communities, white women have reaped the biggest benefit. And yet another case of interest convergence emerged with the legalization of marijuana. Formerly criminalized and associated with communities of color, cannabis is a big business now that provides large profits for dispensary owners (often white), and taxable income for local government. In both of these cases, public policy changed under the guise of racial justice, but the benefactors were not the intended party. And, in some ways, minoritized communities continue to suffer despite policy changes.

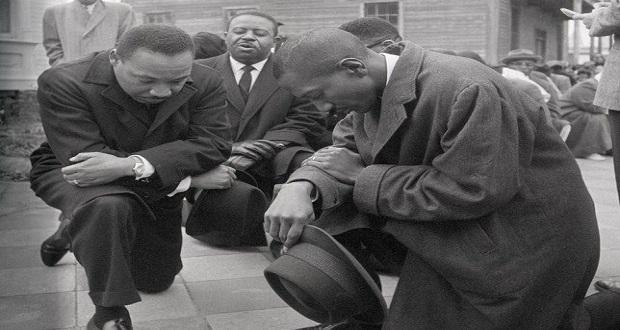

Organizations are not exempt from this phenomenon. Policies and practices that govern hiring, training and professional development, and performance evaluations often represent the interests of the organization’s power brokers. For instance, in the late spring and summer of 2020, protests flooded the streets across the nation and globe in demonstration against anti-Black racism and a number of tragic losses including George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. People were not just protesting these grotesque acts but the tools that bred them, such as white supremacy and institutionalized racism. In a sudden turn of the tide, organizations began posting statements in support of anti-racist work and denouncing anti-Black racism. It would be great to know that these statements were more than an isomorphic attempt at remaining relevant and avoiding backlash, however, organizations have shown time and again that their diversity interests are tied to commodities. Organizations were posting solidarity statements without clear plans of action and even glaring issues related to racist practices within.

Policies and practices that govern hiring, training and professional development, and performance evaluations often represent the interests of the organization’s power brokers. Share on XSocial issues that arise in justice projects, public health concerns, economic development, and public safety underscore the many ways dominant interests guide how society responds. In the age of TikTok, Twitter wars, and cancel culture, we can easily get caught on competing sides of any issue. However, when the cause for racial justice and equity efforts are met with interest for capital gain, prestige, or power, there is the chance of further entrenching marginalized communities in oppressive systems. So, how do we pursue change for the good of those who’ve been harmed, rather than converging interests with false allies? Here are just a few questions to consider when moving through this work:

Whose interests are being prioritized?

Who benefits from this? Who loses out?

How will this make things more equitable?

When the cause for racial justice and equity are met with interest for capital gain, prestige, or power, there is chance of further entrenching marginalized communities in oppressive systems. Share on X