As mentioned in an earlier article, “the work” to us at The Winters Group is “creating transformative and sustainable solutions for individuals and organizations in support of their efforts to create more equitable and inclusive environments.” This series is about exploring those moments when, perhaps, we witnessed an injustice and failed to intervene, or engaged with others in a way that was counter to “the work” we’ve set out to do.

While I cannot recall a time when I failed to intervene to prevent or address an overt injustice, I recall moments as a facilitator when I did not put in place the norms and mechanisms necessary for all people to experience the psychological safety needed to share their truths and experiences around being part of a marginalized or subordinated group. I believe there have also been times when I acted as if my role as facilitator was only to “protect” people of color, women, LGBTQ, and other members of marginalized groups from the biases of members of dominant groups, particularly white men. My inclination to “protect” in some cases stifled opportunity for fostering deeper learning, self-understanding, and reciprocal empathy.

I recall moments as a facilitator when I did not put in place the norms and mechanisms necessary for all people to experience the psychological safety needed to share their truths and experiences. Click To TweetFor example, I facilitate a Winters Group exercise entitled “What Would You Do?” In this exercise, a female Operations Leader seeks to resolve a situation with a white, male leader who, perceivably, has several “blind spots” regarding the experiences of women in their workplace, specifically in the context of the #MeToo Movement. In the scenario he attempts to express his support of the movement, but also shares his concern that it may be stigmatizing “all men,” and even suggests that women should “speak up” more often when experiencing sexual harassment. The “ask” of the group working on the scenario was to discuss the ways in which the female operations leader might prepare for and engage in dialogue with her male counterpart given his lack of awareness.

During the group discussion, one participant, a young white female, recommended the female leader facilitate a focus group of women, or engage the company’s women’s employee resource group, before meeting with her male counterpart to have a better sense of how other women were experiencing their workplace, and perhaps use a leverage point. Almost immediately, a young white male in the room responded: “this suggestion is discriminatory to men—why can’t men and women discuss the situation together without fostering segregation?”

I jumped in and reminded the class of dominant and non-dominant group dynamics, and that there was tremendous value in the women’s resource group discussing the issue among themselves to share their experiences, challenge and learn from each other’s perspective, and arrive at some helpful suggestions for the female operations leader. As a result of this process, when the hypothetical female operations leader met with her counterpart, the discussion could potentially be more fruitful, as she’d be able to leverage her qualitative observations.

My inclination to “protect” in some cases stifled opportunity for fostering deeper learning, self-understanding, and reciprocal empathy. Click To TweetNearly everyone nodded or showed agreement with this suggestion (during a break, the young woman even thanked me for stepping in). Then, many of the women and some men offered thoughts on what the female leader might learn in her discussion with the women’s resource group.

As we transitioned from the exercise, I also suggested the hypothetical female leader might self-reflect on her perspectives regarding men and determine if she could place herself in the male team member’s shoes (e.g. What were the origins of his blind spots? What is the role of masculinity and messages men have received? How might she bridge to cultivate greater awareness?). There was much less discussion regarding this recommendation, and I sensed that some men thought about making a point but then thought otherwise. Because of time restraints, we moved on to the next topic.

So, what work didn’t happen?

I believe it was two-fold—1. There was self-reflection required on my part to better understand my immediate reaction to the young white male’s comments, and 2. Opportunity to understand how I could have facilitated deeper learning and reciprocal empathy between the women and men in the scenario and discussion.

After reflecting, I realized I stepped in quickly to respond to the young, white male’s comment because I felt I had to protect certain people and arguments in that situation. I have since asked of myself, “What aspects of my intersectional identity drove my behavior and why? Why did I feel the need to step in so quickly? Were my motivations those of a facilitator, a male (dominant group/ally), as an African-American (member of a non-dominant group), or all of these? Could this have impeded my capacity to take the individual and group deeper?”

In hindsight, I believe that everyone could have learned more if I had taken the opportunity to help participants piece through what all of the people in the case study might have been feeling—not just the women. By not diving into the perspective of the male character in the case study (even if his reasoning was perceivably misguided and not fully informed), I missed an opportunity to support participants in developing a better understanding of that perspective—one some of them might have shared—and where it comes from. In turn, if these participants were to encounter a similar situation in real life, their response would likely be to negate the man’s perspective rather than explore it with curiosity and see what learning could occur on both sides.

A recent study entitled Millennial Men & Modern Manhood: The Pressure To Be It All, explores some of the challenges young men are experiencing understanding masculinity and balancing it with many of our evolved cultural norms. Oliver McAteer suggests that “men are experiencing a clear tension point between the expectation for them to be empathetic and emotionally connected spouses and fathers, to the equally strong expectation for them to be manly providers for their families. For Millennial men, in particular, this tension seems to be at breaking point; men just don’t seem to know who or what they are supposed to be in 2018 and beyond.”

I believe there could’ve been so much more to learn and unpack around masculinity and the role of men in these discussions if we had gone deeper.

What could the work look like?

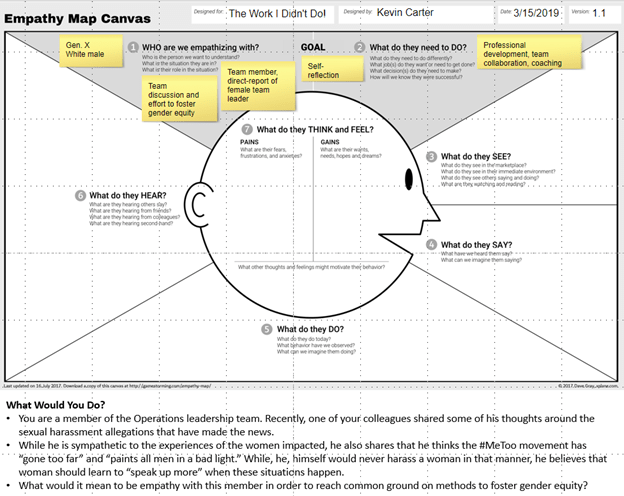

The situation was one of the catalysts for The #MeToo Imperfect Ally assessment and a workshop to be delivered during The Forum on Workplace Inclusion conference, April 17th in Minneapolis. The purpose of the assessment and workshop is to provide a setting and process for all genders to have productive discussions on how to foster gender equity within organizations. Those discussions should be anchored by self-reflection and reciprocal empathy. An empathy map (pictured below) can help us put our intention to be empathetic into action.

An empathy map is a collaborative tool teams can use to gain a deeper insight into their customers. An empathy map can represent an individual, group of users such as a customer segment, or community residents. Dave Gray created the empathy map. Gray offers, “you should be able to make a rough empathy map in about 20 minutes, provided you have a decent understanding of the person and context you want to map. Even if you don’t understand the stakeholder very well, the empathy-mapping exercise can help you identify gaps in your understanding and help you gain a deeper understanding of the things you don’t yet know.”

Below is an empathy map I have started for the exercise to understand the male team member’s perspective. See the latest version of the map here. I encourage you to leave a comment.

How powerful would it have been for members of the class to develop their own empathy map of the situation, share and discuss it at their tables?

I encourage you to develop empathy maps that represent your perspective to share with others and determine if you can answer the questions the map poses for those with whom you desire to empathize.