Imagine being virtually silent for 30 years. Imagine barely speaking to anyone outside of close family and friends. No small talk with the person at the supermarket checkout. No lighthearted chat with the receptionist at the doctor. No comments about the weather with people at the bus stop — simply holding your tongue for 30 years. What would that feel like? Frustrating? Restrictive? Lonely? Miserable? All of these and more, I suspect.

None of us speak freely 100 percent of the time. We may rephrase our frustrations in front of our manager or keep quiet when our client says something we disagree with. But, outside of professional limitations, we white people are pretty free to speak up.

Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) cannot say the same. While reading I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be by Colin Grant, a paragraph about Grant’s mother struck me. Ethlyn had emigrated to England from Jamaica in 1959. She spoke English, but with a Jamaican accent. Grant writes that Ethlyn “became so fed up with English people saying ‘pardon?’ to her whenever she opened her mouth that after a while, she stopped speaking with them altogether.”

Imagine that. Here was a Black woman unable to make herself heard in a predominantly white country. White people had silenced Ethlyn.

We Weaponize Silence

While reading this, I was deeply saddened for Ethlyn. Here was a woman who had moved her life across the world only to be imprisoned by others’ inability to understand her. Such was the force of this inability that she stopped talking.

This image of Ethlyn filled me with shame, too. Because, as a white person myself, I’ve done the same thing. I’ve ignored someone with a strong accent, frustrated when I couldn’t easily understand them, and effectively been dismissive of what they had to say.

This got me thinking about the weaponization of silence. Preventing someone from speaking or being heard is an effective tool of oppression — one that we wield often without realizing.

It’s “without realizing” that’s the crux of the issue. Most of us are wandering through life, trying to do our best. But we’re accidentally harming people and we may not even realize it. So, this article aims to help us white people realize when we silence others. To bring those moments into awareness. Once we’re aware we’re doing something, we can fix it.

I’ve identified five tools we use to silence others, intentionally or otherwise. These are:

- Dismissal

- Denial

- Diminishment

- Disbelief

- Deflection

Let’s take a closer look at each, starting with dismissing Ethlyn’s accent.

1. Dismissal

Making little effort to understand someone speaking with an accent is an effective form of dismissal. Saying “pardon?” or “I don’t understand what you’re saying” are how we show our frustration or impatience, thus communicating that we don’t have time for this; their words are not essential to us.

Many people are intolerant of those who arrive in our country without perfect English. Immigrants who cannot meet this standard often have no choice but to take low-paying jobs in hospitality or retail. Even then, many extend no patience for them to learn the language; they must be fluent instantly or go home. “If you’re here, you should speak the language properly!” people decry thoughtlessly in shops and restaurants, likely never having had to become fluent in another language themselves.

We avoid the water cooler when our colleague with a strong accent is there. It’s too much effort to make small talk when we don’t understand what they’re saying. So, we take the easy way out and steer clear. Ultimately, others avoid this same colleague. Soon enough, the colleague gets the message and stops trying to engage. No one appears interested in what they have to say. Their attempts to integrate and learn the language have fallen at the water cooler. They’ve been silenced.

2. Denial

Another tool we use to silence people of color is to deny their experiences. We reject their reality and shun their suffering. Instead, we claim that it never took place, positioning ourselves as the authority on race.

I see this online when someone shares their story of everyday racism. Frequently, comments from white people outright deny that these encounters occurred or that race was a factor.

The thing is, as white people, we view the world differently. We rarely, if ever, face overt or covert racism. We’re so cocooned in our bubble that we don’t recognize it even when it’s right in front of us. This means that when a person of color speaks out, their experience is foreign to us, and we may tend to deny their truth. We fail to see that not everyone encounters the world the same way we do, that we hold privilege, and that other people’s lives are different from ours. Rather than recognize this difference, we reject their reality. When we deny someone else’s reality, we silence them.

3. Diminishment

The third way that we white people weaponize silence is by diminishment. We minimize the experiences of others.

Imagine your colleague tells you that a mutual co-worker said something racially offensive. You reply with, “I’m sure they didn’t mean anything by it,” or “Really? That doesn’t sound like them.”

Comments like this play down racism, and belittle it. While they may be well-intentioned, they undervalue what people of color go through and lessen its importance. When we try to explain away a co-worker’s offensive statement, we’re insisting that the offended person must be wrong. Insisting someone’s wrong effectively silences them.

4. Disbelief

The fourth tool we use to silence BIPOC colleagues is not believing them. This takes two forms: outright disbelief — “that didn’t happen” — or expressing shock. I’ve covered the first in Denial. Now, I’ll focus on the second, expressing shock.

This is when we convey surprise at racial discrimination. We’re outraged, exclaiming, “I can’t believe this still happens in 2023!” It’s a rude awakening for us, an eye-opener. We’re incredulous that racism still occurs, and we struggle to believe it.

Expressing shock further demonstrates the bubble in which we live. We’re so protected that we have no idea this happens or is so prevalent. So, when someone brings it up, it is jarring to us and our experiences. This reaction reinforces that racism is so very salient for others, yet not for white people. This is a privilege.

5. Deflection

The final way we silence our BIPOC colleagues is by deflection. This is when we swerve the conversation to something else, often to one-upmanship. For example, your colleague tells you that someone in their team made them uncomfortable. Your reply is, “You think that’s bad? Last week, I got written up for speaking my mind to that client. You remember the one …” and on you go, with a story about you.

When we change topics, we tell the other person that their story doesn’t matter. Compared with what we’re going through, they’ve got it easy. This minimizes their experience and its importance. If people don’t feel like their story matters, they will stop sharing it.

Silence Serves Our Comfort

Why do white people silence others intentionally or otherwise? Well, for most of us, talking about race is uncomfortable. We often don’t understand the nuances that people of color navigate every day. We’re racially illiterate. So, any talk of race or racism makes us uneasy, and we don’t like to feel uneasy.

Avoiding discomfort is a normal human response. We dislike awkward situations. We feel restless, on edge, and rattled. We’re tense and will go to great lengths to wriggle out of these conversations.

And wriggle we do.

We use any means necessary to rid ourselves of our discomfort. First, we shut the conversation down by dismissing, denying, diminishing, disbelieving, or deflecting. Then, we bring it back to where we’re at ease.

The conversation moves away from them and onto us. “I don’t understand what you’re saying”; “I don’t believe you”; “I’m sure they didn’t mean anything by that”; “I can’t believe this still happens in 2023”; “Last week I got written up ….” We center ourselves. Because when the conversation is about us, it’s comfortable. We’re in control, and our discomfort disappears.

Therefore, rather than awkwardly listening to our BIPOC friends and colleagues, we seek comfort. This unintentionally pushes them into a Spiral of Silence, and they stop talking.

The Spiral of Silence

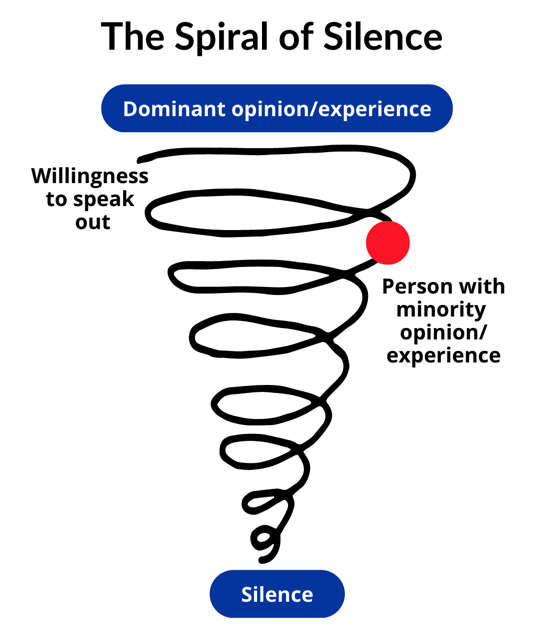

The Spiral of Silence is a well-documented communication thesis. It demonstrates that people don’t express their opinions if they feel like those opinions are in the minority.

The diagram shows how people start off willing to speak out. This decreases each time they voice their minority opinion or experience. Eventually, they stop speaking about it altogether, and the dominant view or experience prevails.

Because whiteness is a dominant identity group in the context of white supremacy, white experiences dominate and voicing other experiences can be arduous. After being repeatedly dismissed, denied, diminished, disbelieved, and deflected, this experience becomes harder to express. Hence, people of color stop talking about it altogether. And if they’re not talking about it, then we’re not hearing it.

Ultimately the Spiral of Silence contributes to why we believe racial discrimination is rare. We don’t hear enough about BIPOC experiences. This reinforces a false impression that racism has stopped.

Power and Privilege Reinforces a Vicious Cycle of Silence

Our white privilege feeds a cycle. Our unintentional silencing has:

- Discouraged BIPOC from talking about experiences of racism

- Created the illusion that racism is rare

By prioritizing our comfort and silencing others, we stop hearing about systemic racism. But unfortunately, this leaves us with a distorted view of reality. We’ve created a false narrative where racism doesn’t exist anymore. It’s a relic, confined to the past, left in history.

White people do not experience racism. No microaggressions; no casual dismissal of our lives; no heavy-handed manager being harsher to us than the rest of the team; no one making us feel like we don’t belong by asking, “but where are you really from?”; no “You’re so exotic”; no race-based discrimination from doctors, lawyers and bankers.

What’s left is the white experience — a life free from systemic racism. (And more insidiously, too often free from mention of it.) So, the white experience becomes the only one we hear about. To those of us living it, it seems universal, the standard. Our worldview becomes the only worldview.

This is what white privilege is, a bubble of protection from systemic racism.

What Can We Do?

Once we have all of this insight, how do we move forward? What do we do about our silencing? The solution is simple. The first step is awareness. It’s noticing when we use the five tools of silence. As with all things, seeing them in others is easier than catching them in ourselves. But see, we must.

However, awareness is just the first step. The second is action — or, more accurately, inaction.

We stop saying these things. Stop dismissing, denying, diminishing, disbelieving, and deflecting. Which sounds pretty simple, doesn’t it? Except, when we stop, we’re left with a big, uncomfortable hole in the conversation. One where the other person is talking about racial issues that make us uneasy. This is the tricky part: recognizing our unease and sitting with it.

The simplest way to do this is to engage with what the other person tells us in a way that centers their experiences. It’s helpful to remember: They’re speaking their truth; while what they’ll be saying may be outside of your field of reference, trust that they understand their own experiences better than you do. This will help us overcome our discomfort and focus on the other person.

Conclusion

It can be tempting to believe that we always act thoughtfully and considerately and don’t perpetuate harmful ideologies. But, when white people examine our interactions with people of color honestly, we are likely to find that’s not always the case. We may cause harm, even if it’s accidental.

This can be a difficult realization. Rather than beat ourselves up with this uncomfortable truth, let’s put our awareness and insight to good use. Let’s notice when we dismiss someone’s accent or deny their reality. Let’s avoid diminishing another person’s experience or exclaiming that we don’t believe them. And let’s be alert to all the times we deflect the conversation from them to us.

We’re never acting well when we’re wriggling out of discomfort and awkwardness. We’re being selfish. Instead of accidentally pushing our co-workers into the Spiral of Silence, let’s hold space for them to speak. Let’s listen to what they have to say and believe their stories. If we all do that, we’ll see change in the workplace and beyond.