As the month of February approached and I prepared for Black History Month, thinking of possible activities I could facilitate and participate in, it was not lost on me that right in the middle of the month is Valentine’s Day. I felt inclined to plan around the holiday to ensure that I didn’t interfere with lovers’ plans. However, that feeling didn’t quite sit well with me. Valentine’s Day is a commercial holiday that is predicated upon centuries old stories about love and sacrifice, and heart-shaped candy and cards. Certainly, the celebration of Black History Month necessitates a deep level of reflection and provokes action in such a way that supersedes a calendar day and a temporal display of affection. Or does it?

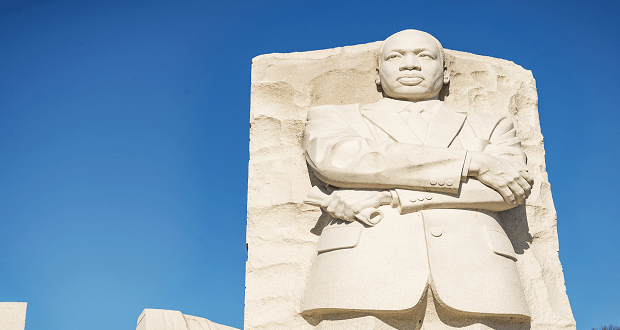

Recent events illustrate disdain and even violence towards Black Americans. From the rejection of the College Board’s AP African American History course (and, later, their concession to strip away important facts about Black history), to the murder of Tyre Nichols, we see the open attack on Black intellect, Black histories, and Black bodies. In the recent Hulu series based on Nikole Hannah-Jones’ work, The 1619 Project, Hannah-Jones describes the depth to which anti-Blackness is embedded in every facet of American society from politics, to housing, to music, to everyday life. And Hannah-Jones herself, as a critically acclaimed, award-winning journalist scholar, has received an overwhelming and unconscionable amount of backlash for simply telling the truth about Black history in America.

Even as this country celebrates Black History Month every February, there seems to be an astounding hate for Blackness and Black people. Seemingly the furthest away from “America’s sweetheart,” Black people continue to love and embrace America. Our ancestors have not only fought in this country’s wars and been instrumental in the construction of this nation, we are as deeply invested as other Americans in the righting of this place we call home.

The writer James Baldwin’s words, though long ago, remain relevant and imbue the deep commitment and patriotic sentiment evident in the fight for Black lives to matter:

“I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” What Baldwin was talking about is what I think Black Americans still desire today — to be loved, respected, and to be seen as fully human.

It can be easy to reduce the relevance of Black history to one month a year or even conflate Black History Month’s recognition with that of Valentine’s Day when the celebration has been commercialized. However, recognizing the humanity in others, and specifically, honoring Black people and their contributions to this country requires compassion and is an act of love.

So, in your (ongoing!) celebration of love and Black history, remember to reach beyond retail and taglines to:

Learn about Black history — American history.

Celebrate Black Joy.

Recognize Black humanity.

Challenge anti-Blackness.

Love and respect Black people.