I was in my local spice shop this weekend and was touched to see a small handwritten “Ramadan Mubarak” sign. Across the Atlantic in the U.K. — the country of my birth — Ramadan lights went up for the first time in London’s Piccadilly Circus. Over the past week, I’ve received a steady stream of messages from my non-Muslim friends wishing me a happy Ramadan. And in the middle of writing this article, my partner texted me that KQED — our local NPR station — was doing a whole segment on Ramadan foods.

As a practicing Muslim, these gestures both alight and heal my heart. The hurts I have accumulated over a lifetime of subtle and overt Islamophobia are not insignificant.

And while Islamophobia’s presence in our lives persists, I appreciate the growing awareness among non-Muslims about this tradition.

However, even amidst the increasing attention around Ramadan, there is still an essential piece that’s missing. So much of the information shared about Islam’s holy month focuses on the mechanics: abstaining from food and drink (“not even water?”… a now ubiquitous phrase of internet memedom) from sunrise to sunset for an entire month.

Don’t get me wrong; the technical aspects are extremely important. But there is a tendency with narratives surrounding Islam in particular to turn it into a distant and static object. In his 1978 book, Edward Said offered his analysis on the concept of Orientalism: a portrayal of Islamic civilization as the quintessential “other,” in contrast to a supposedly advanced and enlightened Western society.

In the simplest terms, focusing on the mechanics of Ramadan not only perpetuates “othering” of the Muslim community, it shortchanges a deeper understanding of the tradition.

As Muslims, we are guilty of falling into this pattern ourselves. The essence of Ramadan is hard to describe. It is part celebration, part holy season. It is a time of coming together and also a time of solitude and reflection. In being asked to describe what feels indescribable, it feels easier to focus on the mechanics. Add on a fear that extolling Ramadan’s inner meanings might be misunderstood as proselytizing and the fact that, in a community of over 1.7 billion, what people understand as the “inner meanings” of Ramadan varies, it seems better to stick to the observable facts.

Yet, I feel strongly that the essence of Ramadan is for all of us.

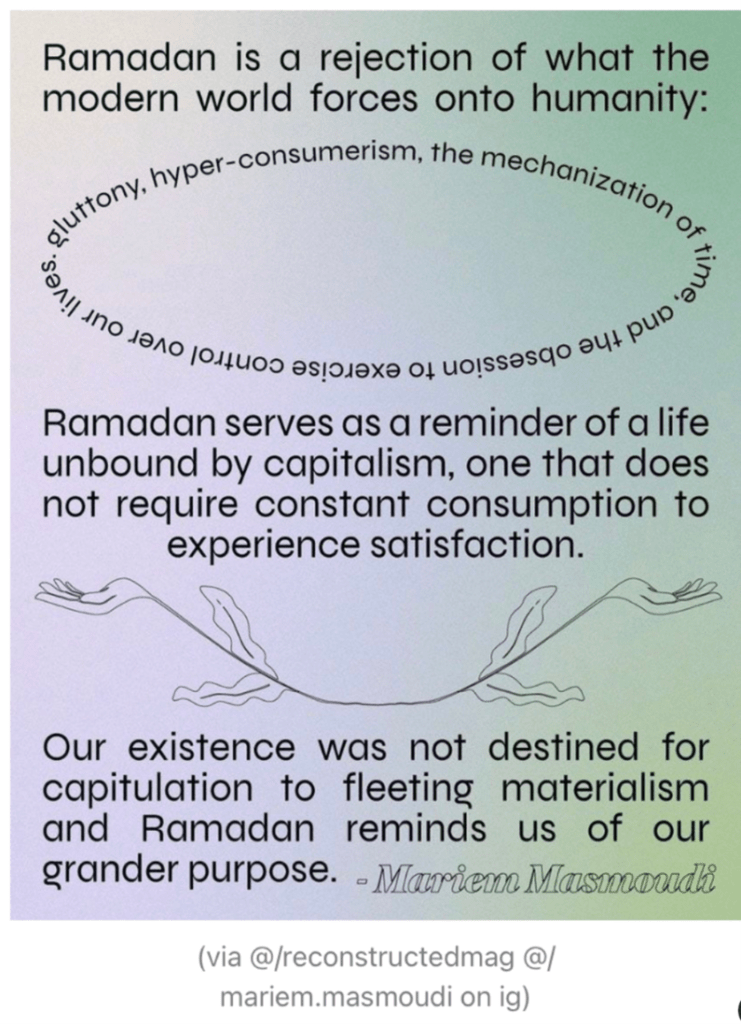

We are living in a time of intense disconnection and destruction. Excessive consumption has our minds, bodies, spirits, and planet on the brink. Ramadan is an invitation to heal and step into another way of being with the world and one another. And this is my invitation for all to join me — whether or not you fast, practice Islam, or have any religious inclinations whatsoever — in contemplating the essence of Ramadan.

So, what is this “essence”? And what does it mean to participate in Ramadan’s transformative change? To me, it begins with a sincere contemplation of three elements: our relationship to our bodies, our relationship to consumption, and our relationship to community.

How are you partnering with your body? How are you embodying your values?

The body and spirit connection in Islam is profound; the two aspects are inextricably linked. While fasting, I personally feel much more embodied. I feel my humanness; I feel deeply aware and appreciative of my body. The body is not an obstacle to overcome, it is a partner in the spirit’s journey. The fast is not a punishment of the body but an acknowledgment of this sacred partnership. (And, thanks to the intermittent fasting trend, there’s a growing body of research on the healing benefits of this practice as well).

Ramadan also reminds us of our place in the natural world. In contrast to the Descartian worldview of, “I think, therefore I am,” Ramadan reminds us, “I feel, therefore I am.” To feel the pangs of hunger and thirst is to feel the weight of our profound interconnectedness, a reminder of survival’s common denominator — the need for food and drink — connecting every single human and living being on this planet.

What is possible in your life when you decenter consumption? How much do you really need?

Ramadan disrupts and decenters consumption as the central pillar of our lives. When you take food and drink out of the equation — during daylight hours — it cracks open your routine and pushes you to deeply consider how you want to shape your day and what you truly value. The fast also requires intentionality around what we’re ingesting in all aspects. What are we putting into our bodies via our ears and eyes? In the overstimulation of our tech-centered lives, slowing down and staying in choice around what to consume is a balm for the mind, body, and spirit. In creating distance in our relationship with consumption, we create space for other relationships and priorities.

How and where can you support reciprocity in your community?

Ramadan is also a time of redistribution and reciprocity. This is the season where Muslims calculate their resources and give a portion of their assets to community members in need. This practice, called Zakat, is founded on the central notion that nothing truly belongs to or comes to us via our individual efforts alone, and, as such, must be shared. Zakat parallels the process of fasting. With the fast, the body is consuming less and redistributing its energy and focus. Materially, we bring that process to life by giving from whatever wealth we have accumulated. In this way, we practice Zakat with the entirety of our being. It is a way of embodying our commitment to community; sweeping away excesses in order to draw closer to our community.

These reflections are but a small snapshot of Ramadan’s multifaceted inner landscape. The external ritual of the fast is a protective layer; a husk holding a seed’s tender core and multiple meanings. When the fast ends and the husk gives way, what springs forth is a deeper, embodied understanding of our sacred obligations to the Divine and to one another.

Muslims comprise almost a quarter of the world’s population. We exist in every corner of the globe. Ramadan is our annual reminder of who we are and who we belong to; it is a gift that nudges us, collectively, toward a healthier and more balanced life. And while gifts can be personal treasures, they are best appreciated when shared with others.

* “God knows best.” You will often hear Muslims say this phrase after sharing any religious learnings as a way of recognizing human fallibility in our interpretations. To me, it’s also a way of acknowledging the multitude of experiences, expressions, and perspectives within an incredibly diverse Muslim community. Thank you for considering mine.

What a refreshing article to read! After observing 40-days of holy Lenten season where I was invited to fast, pray and do almsgiving, with in-depth awareness of our broken humanity and how to be more in touch with our “neighbors” so to bring us closer to our creator, it’s so beautiful to see this continuing of invitation to be aware of our community and its own humanity needs through my Moslem brothers and sisters who are observing Ramadan. Wouldn’t be amazing if each faith communities have these on-going holy months throughout the year? I was born and raised in Indonesia before migrated to US. So observing Ramadan is part of my upbringing, although I am not necessarily a Moslem myself. I missed this when I came to US.

Thank you for posting this beautiful article. A very Blessed Ramadan! ❤️