The following was taken from a chapter that I contributed (From Diversity to Inclusion: An Inclusion Equation) in the recently released book, “Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion” edited by Bernardo Ferdman and Barbara Deane (Jossey-Bass, 2013).

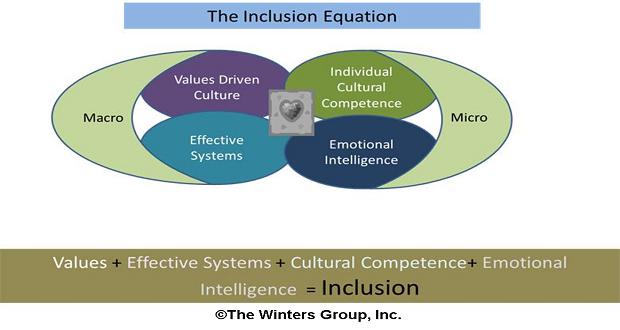

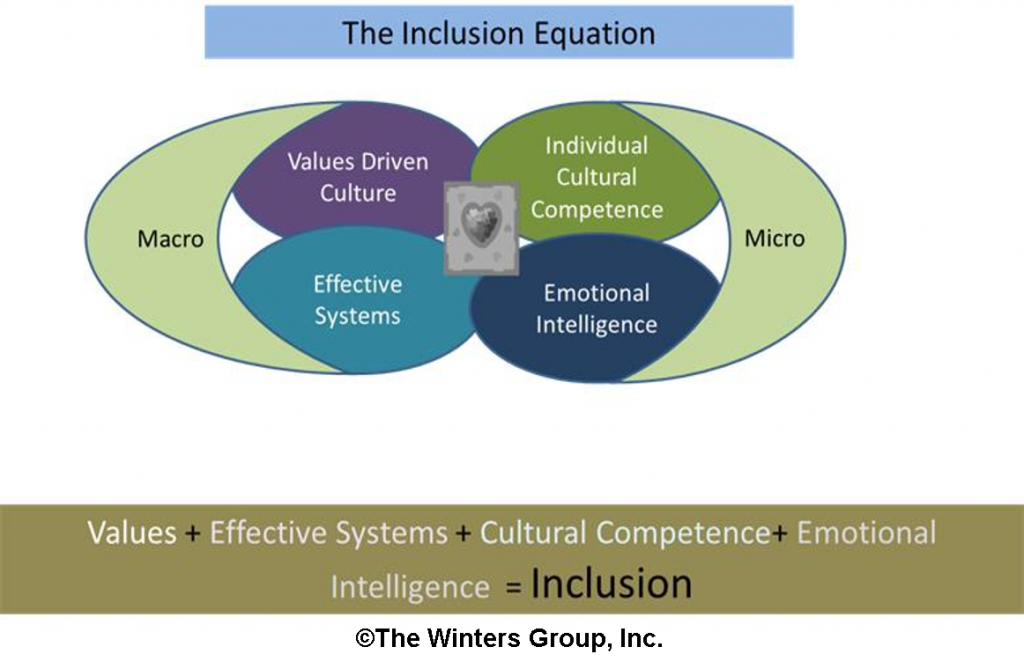

Last week I posited that inclusion is simultaneously about the macro (systems and values) and the micro (individual behavior). Inclusion is most effectively driven both via top-down leadership and bottom-up engagement. I introduced the Inclusion Equation that I repeat below.

Last week I explored the macro parts of the equation. This week I will provide more detail on the micro elements.

In my 2002 book entitled Inclusion Starts with I (Winters, 2003) I assert that inclusion begins with the individual. An inclusion mindset often requires transforming the way one thinks and behaves. From her book You Learn By Living Eleanor Roosevelt sums up this sentiment for me.

You must truthfully understand what makes you do things and feel things. Until you have been able to face the truth about yourself you cannot be really sympathetic or understanding in regard to what happens to other people.

Over the past 25 years, organizations have put substantial effort into training, especially for those in leadership positions, with the goal of shifting thinking and behavior to be more inclusive. However, in my observation, short term training is inadequate to build skills and shift mindsets.

Those with the power to drive inclusion must want to do it. No amount of coaching, coaxing, or coercion can convince the die-hard recalcitrant. Leaders have to believe in diversity and inclusion, either as part of an altruistic goal, and/or because they truly believe inclusion will enhance business success and in turn make them better off in some way.

Inclusion will not be sustained by leaders who respond to diversity and inclusion initiatives as “check the box” exercises.

The two elements at the micro level are individual cultural competence and emotional intelligence. Dr. Mitchell Hammer, owner of the Intercultural Development Inventory® (IDI®), a tool which measure intercultural competence defines intercultural competence as:

The capability to shift cultural perspective and adapt behavior to cultural commonality & difference in order to successfully accomplish cross-cultural goals. Such capability is developmental and it is learned.

Modern management theory now widely accepts that effective leaders must possess more than technical expertise to engage employees and achieve business goals. Daniel Goleman, one of several EI theorists, asserted in 1996 that one’s EI is a greater determinant of success than one’s IQ (Goleman, 1995). Goleman identified the five domains of EQ as knowing your emotions, managing your own emotions, motivating yourself, recognizing and understanding other people’s emotions, and managing relationships, i.e., managing the emotions of others.

Lee Gardenswartz, Anita Rowe, and Jorge Cherbosque formed the Emotional Intelligence and Diversity Institute in 2004 to promulgate the connection between emotional intelligence and inclusion. They developed a model focused on introspection and self-governance, intercultural literacy and social “architecting” as a way of serving as a cultural interpreter. Cherbosque, Gardenswartz and Rowe’s definition of Emotional Intelligence and Diversity (EID) expands the traditional definition of Emotional Intelligence so that it is relevant in today’s diverse world. EID involves the ability to feel, understand, articulate, manage and apply the power of emotions to interactions across lines of difference.

Achieving and sustaining inclusion is not easy. It takes intentional, concerted, ongoing effort. Inclusion will only be sustained when all of the elements are working synergistically, both at the micro (intercultural competence and emotional intelligence) and macro levels (systems and values).