As Catalina Pinto introduced last week, this feature series will explore the times when we failed to do “the work”—acting for diversity, equity, and inclusion in our own lives. Even as D&I practitioners, we remain imperfect, and reflecting on where we could have acted differently can help us to identify our personal challenges in “the work” and do better in the future. When I reflect on “work I didn’t do,” there are two experiences that feel particularly salient.

During undergrad, I was working at the preschool on my campus as a teacher’s assistant. My lead teacher was out sick and a substitute was working in her place. While we supervised the playground activities, she was telling me about how her kitchen was being remodeled. She shared that she and her husband were about to leave on a trip. She was nervous and “not to sound racist but…” expressed apprehension leaving her home due to the workers’ ethnicity and was concerned about leaving valuables in her home while she was traveling.

The preface, “Not to sound racist but…” presents an ideal opportunity to interrupt the person speaking and suggest something like, “please reconsider finishing that thought.” Not only did I miss that opportunity, I also missed the opportunity to respond and challenge this racist idea after it was expressed, remaining surprised but silent.

There were at least two reasons for my inaction in this moment. First, it was one of the first times in my adult life that I had recognized explicit racism expressed in person. It caught me off guard, and I was so surprised enough to hear it that I wasn’t prepared to respond. Needless to say, it speaks to my privilege that I was able to reach adulthood before recognizing an explicit expression of racism in real time.

Secondly, there was a power dynamic at play. She was a lead teacher, a good 30 years my senior, and I was a 19-year-old work study student, and her assistant for the day. While I may have been more comfortable challenging my peers on difficult topics, I found my confidence missing as I wondered (with no clear answers) what my role was here and how our different levels in the organization could or should play into any response I offered.

In failing to respond productively, I implicitly endorsed her comment as acceptable, and I have regretted this moment ever since—particularly considering the harmful effects that her unchallenged racial biases could have had on her engagement with the young learners she was tasked with teaching. In hindsight, I vowed to do better in the future.

The second situation I want to reflect on occurred several years later, while I was walking past a bus station. I noticed an argument between two apparent strangers waiting for a bus. “You can’t say that to me!” the woman said, clearly upset. The man hurled back a racial slur, insisting, “I can say it!”

I was upset to hear this exchange, and my first thought was that, “I should stop.” But then, my brain started composing excuses. “I need to catch a bus,” came first, then, “I don’t know for sure what’s happening, I just walked in in the middle of this exchange.” Next my thoughts turned to fears for my own safety were I to intervene, and finally, to something to the effect of, “this isn’t about me.” I deeply regret it, but confronted with all of these factors, I kept walking.

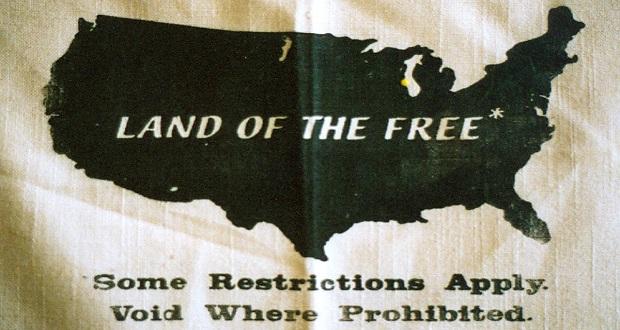

In one very literal sense, I was right about the last statement; as a white 20-something on my way home from a study session to a quiet evening, the stakes were low for me personally…but that didn’t excuse me from stepping in to help. If anything, I believe my privilege of not having had to deal with racism directed toward me and my identity gave me more responsibility to use my power in that situation and show another white person that his behavior was unacceptable. Instead, in that moment, I chose to prioritize my own convenience over intervening in a way that could have substantially changed the situation. And I was decidedly wrong in concluding that this “wasn’t about me” in the sense that I was actively upholding white supremacy as I passively walked past.

A large body of research has demonstrated that changing people’s perceptions of social norms in a situation can drastically shift their behavior—for better, or for worse. Each time that a harmful or xenophobic comment goes unchallenged, it is validated as being acceptable to express. My active response in this situation might have caused this individual to think twice about publicly expressing similar sentiments in the future.

Each time that a harmful or xenophobic comment goes unchallenged, it is validated as being acceptable to express. Click To TweetYet, most upsetting to me when I thought back to this moment, was the fact that, because of my silence, a woman of color who deals with micro and macro aggressions daily was left, again, to feel that much more alone in a moment of frustration and hurt—likely one of fear as well. Particularly in the context of a socio-political climate that feels on the brink of sliding into a space where bigotry is acceptable to express in more places than not, the impact of my inaction was, in my view, substantial. There is a lot I would give to have that moment back.

Shortly after my experience at the bus stop, I took an opportunity to participate in a bystander intervention training. I learned tactics that increased my confidence for stepping in to address a situation like the one I had found myself in:

- Pause to assess the situation and gain a better understanding of what is happening.

- Assume responsibility for taking action.

- Know the appropriate way to respond, considering your own safety. In many situations, experts recommend humanizing the person who is the target of the harassment by engaging with them, rather than the harasser, though the latter is many people’s first instinct.

Newly armed with practices and strategies that were designed to pre-empt many of the rationalizations that held me back at the bus stop, I left feeling more prepared to recognize and intervene in a problematic situation the next time I encountered one. I recommend completing bystander intervention training to anyone invested in “the work” for this reason exactly.

My reflections on these moments where my actions didn’t align with my values and convictions, and my regrets about this, as painful as they first felt, has helped me to avoid making the same mistakes over again. Disrupting injustice is an active process, and often feels uncomfortable. It’s easier to do nothing, but Desmond Tutu’s timeless words remind us, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” I seek to avoid this pitfall personally and professionally; yet, I am, like all of us, imperfect. But burying our mistakes does not help us to grow or learn. I invite and encourage us all to do the necessary work of self-reflection to more consistently promote and bring about the equity and justice that we are seeking.

Burying our mistakes does not help us to grow or learn. I invite and encourage us all to do the necessary work of self-reflection to more consistently promote and bring about the equity and justice that we are seeking. Click To Tweet